Three women mystics of 13th-14th century Europe recorded their spiritual experiences. All were women on the margins of society and church (two were Beguines and one was an anchoress). All reflected on the movements of the Holy Spirit (in the world and in their own lives). All wrote about the love and compassion of God (rather than focusing on God’s judgment). All wrote in their native languages (rather than in Latin) which made their works accessible to ordinary readers. Mechtild of Magdeburg wrote Flowing Light of the Godhead in an early German dialect; Marguerite Porete wrote the Mirror of Simple Souls in early French; and Julian of Norwich wrote Revelations of Divine Love in middle English.

TWO BEGUINES

The Beguines were women attempting to live a holy life on their own. Rather than moving into convents like women of previous generations, they chose to live on their own or in informal Beguine communities. As early as the 12th century, they were harassed by the church (because they were not under its control) and most had disappeared by the early 14th century. (However, the last surviving Beguine died only a few years ago, and travelers can still visit the home where she lived in Belgium).

What inspired the rise of the Beguines? The church reforms of the 11th-12th centuries inspired men and women to imitate the life of Jesus and his first disciples. But convents were now overcrowded as monks, reforming their own way of life, closed convents attached to their monasteries; so women were looking for a place to live a holy life. Many were living alone, because their men had died in various wars, or had left on the crusades. As the European economy improved, a middle class was developing and it became possible for some women – who had access to property and money – to support themselves.

The Beguine way of life: These women supported themselves with family money, through their own manual labor, or through teaching. Unlike women enclosed in convents, the Beguines took no vows, and thus they lived without clergy supervision. (Their unsupervised life greatly distressed church leaders, who didn’t know how to exert control over them.) By 13th century Beguines often lived in communities; others lived alone; and many were itinerants, begging alms as they traveled.

Beguine influence: The lives, teaching, and writings of the Beguines elevated the status of women in society. They influenced Saints Francis and Clare in northern Italy (eventually accepted by Rome); as well as the Cathars and Waldensians (declared heretics by the Church) of France and central Europe. Their mystical writings influenced later mystics, such as Meister Eckhart.

Mechtild of Magdeburg

Mechtild of Magdeburg (1210-1285)

When Mechtild was 12 years old, she felt God visiting her daily, and by her early 20s she had moved into a Beguine community. She may have been the superior of that community, and is known to have many supporters in town In her 40s, she told confessor about her spiritual experiences, and he commanded her to write them down. (This was a pattern for women mystics – being told to write by confessors; this approval made them far less subject to harassment by the church.) In her 60s Mechtild moved to Helfta, where she kept on writing. Her writings were rediscovered 1861.

In the Flowing Light of Godhead, Mechtild reflects on her spiritual experiences:

• God is love.

• Since our souls are embodied, we only experience God’s presence for short times.

• In between these experiences, our longing for God becomes suffering.

• Suffering also comes from an inability to do all the good we might do.

• The contemplative life is the foundation for the active, compassionate life.

• We must renounce all bodily and material things, but especially our wills, which prepares our soul for union with God.

• Mechtild emphasizes we must give our wills entirely to God.

• When a soul is in union with God, there’s no distinction between God and self, because they share the same nature – which is love. (This is a more radical position than earlier mystics.) From The Flowing Light of the Godhead, Book 1

The Desert has Twelve Things (translated by Frank Tobin)

You should love nothingess.

You should flee somethingness

You should stand alone

And should go to no one.

You should not be excessively busy

And be free of all things.

You should release captives

And subdue the free.

You should restore the sick

And yet should have nothing yourself.

You should drink the water of suffering

And ignite the fire of love with the kindling of virtue:

Then you are living in the true desert.

(translated by Frank Tobin)

The Sevenfold Path of Love, the Three Garments of the Bride, and the Dance

((translated by Jane Hirschfield)

I cannot dance, Lord, unless you lead me.

If you want me to leap with abandon

You must intone the song.

Then I shall leap into love,

From love into knowledge,

From knowledge into enjoyment,

And from enjoyment beyond all human sensations.

There I want to remain, yet want also to circle higher still.

A fish cannot drown in water,

A bird does not fall in air.

In the fire of its making,

Gold doesn’t vanish:

The fire brightens.

Each creature God made

Must live in its own true nature;

How could I resist my nature,

That lives for oneness with God?

Marguerite Porete

Marguerite Porete (d 1310)

Little is known about Marguerite except that she was a wandering Beguine, and that her book, The Mirror of Simple Souls, was written by 1295.

The Mirror of Simple Souls: Marguerite’s book is a dialogue showing how the human soul can ascend to God, who is love. Like Mechtild, Marguerite says the soul must annihilate the will in order to unite with God. However, Marguerite takes the idea further. The simple soul must will nothing, shouldn’t even will that she should live according to God’s will. Contemplation and detachment are everything. Action is a lower step on the way to unity with God.

Marguerite describes the soul’s progress this way: A soul… who is saved by faith without works… who is only in love… who does nothing for God… who leaves nothing for God to do… to whom nothing can be taught… from whom nothing can be taken… or given… and who has no will.

The soul ascends to God through 7 stages:

• The soul receives grace, God tells her to love with whole heart, love neighbor as self.

• The soul abandons herself in mortification of nature.

• The soul loves, does good works, but then abandons good works because love asks to give up what’s most loved, and learns to submit her will.

• The soul is in ecstasy of love, thinks nothing better, but

• The will is a gift from God, and must be given back, so feeling of love departs.

• Soul no longer aware of self, nor God. But God sees Himself in her

• and this eternal glory can be known only when soul leaves body.

Why did Marguerite suffer much more severe persecution than Mechtild? She was a threat to the established order. Unlike Mechtild, she was a solitary Beguine, and had no confessor to give approval to her work. (She did have three experts read her work, but one thought the book might make the weak despair.) She didn’t claim to have received a direct message from God (although like Mechtild she claimed the weakness of females invited God’s goodness to them).

Sometime after 1295 her book burned by bishop of Cambrai, and she was ordered to stop promulgating it, but she refused to stop. The Inquisitors thought her ideas led people away from the sacraments; they compared her with the ‘Heresy of the Free Spirit’, leading people to think they need do nothing (not even lead ethical lives) to unite with God. But she refused to speak to the Inquisitors and was burned on June 1, 1310.

From A Mirror for Simple Souls, Chapter 122

Two stanzas from “Here the Soul Begins Her Song” (translated by Ellen Babinsky)

I used to be enclosed

in the servitude of captivity,

When desire imprisoned me

in the will of affection.

There the light of ardor

from divine love found me,

Who quickly killed my desire,

my will and affection,

Which impeded in me the enterprise

of the fullness of divine love.

Now has Divine Light

delivered me from captivity,

And joined me by gentility

to the divine will of Love,

There where the Trinity gives me

The delight of His love.

This gift no human understands,

As long as he serves any Virtue whatever,

Or any feeling from nature,

through practice of reason.

THE ANCHORESS

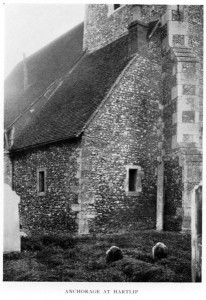

An anchorhold at Hartlip Church in southern England

The anchoritic life is one of the earliest forms of Christian monastic living. Anchorites withdrew from society to lead intensely ascetic, prayerful, and (circumstances permitting) Eucharist-centered lives. In the Middle Ages, anchorites committed themselves to living permanently in little cells; they were enclosed in their cells after a rite of consecration that closely resembled the funeral rite – after which they were considered ‘dead to the world’, and examples of living saint.

An anchorhold was often attached to the outside wall of the local village church. From within their cells, anchorites could hear Mass and receive Communion through a small window in the wall facing the sanctuary. There was also a small window open to the outside world, through which they could receive food and other necessities and, in turn, provided spiritual advice to visitors.

Julian of Norwich has become the best-known anchorite of the Middle Ages. The church never challenged Julian’s theology or her authority to write – even though her views were not typical of mainstream theology – because of her status as an anchoress.

Julian of Norwich

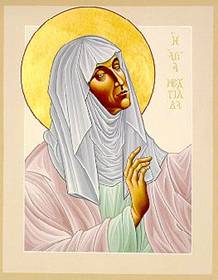

![]()

Julian of Norwich (1342 – 1413)

Julian lived in a time of great turmoil, but her theology was optimistic. In her Showings, or Revelations of Divine Love, she described God’s love in terms of joy and compassion, not rules and duties. She wrote, “The meaning of God is love, and God’s love will triumph.” She believed that loving is not something God does alongside other actions, but that love is all that God does. Her own mystical visions revealed God holding the world in the palm of his hand, as she might hold a hazelnut in her own palm; it led her to believe that God loved and wanted to save everyone.

And in this he showed me something small, no bigger than a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, and I perceived that it was round as any ball. I looked at it and thought: What can this be? And I was given this general answer: It is everything which is made. I was amazed that it could last, for I thought that it was so little that it could suddenly fall into nothing. And I was answered in my understanding: It lasts and always will, because God loves it; and thus everything has being through the love of God.

The popular theology of Julian’s time assumed that God was punishing the wicked, through the repeated plagues and continuing wars experienced in the terrible fourteenth century. But Julian suggested that behind the reality of hell there is an even greater mystery, the mystery of God’s love. Julian believed that sin is the slide into a sense of worthlessness, despair, and self-absorption; sin is forgetting the true value of one’s creation.

Julian knew the church’s teaching about original sin, but she still clung to the goodness of each person’s central essence. She begged God to help her understand why God continues to love when humans fall into sin. God then revealed a parable about a lord and his servant:

A servant sets off on an errand for his lord, but falls into a ditch; he cannot get out, so he loses heart and begins to feel utterly worthless. In his self-absorption he forgets that the lord loves him – and that he had loved the lord – and he falls into despair. This is how Julian understands sin: we forget that we are loved, which leads us to self-absorption and feelings of worthlessness. But God, out of God’s very nature, continues to love us. The servant in the ditch couldn’t help himself, but the lord could. He finds his servant in the ditch, heals him with his grace, and then rewards him with love.

Julian’s theology developed, not from abstract principles (as in scholastic thinking), but from her own experiences. She used female language for God as well as the more traditional male pronouns. She herself had experienced God as compassionate and loving, and she compared Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving, and merciful. For Julian God is ‘the motherhood of grace,’ and ‘motherhood at work’.

Julian’s teaching never became part of the theology of the mainstream church. But, after her decades of contemplation on the mysteries of God and humanity, her theology seems a most appropriate symbol for the way God nurtures all with the mystery of love. Her great saying, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well”, reflects her understanding of God’s love.

ALL THESE MYSTICS CALLED FOR COMPASSION

These women called for, and exemplified, Christ’s work of compassion in the world around them. As practical ministers – as well as theologians, writers, and spiritual guides – they focused on Jesus’ compassion and called for compassion from the organized church of their own day. If there is a common theme that links these women writers, it is that they found compassion lacking in the church’s ministry.

What is the role of compassion in your theology?

… in your thinking about God?

… in your thinking about the society we live in?

… in your thinking about the church?

I often despair at the multitude of wrongs in current developments in our society. I used to believe in progress, but I cannot any more. Quite likely we are destroying the earth and all living things. But I try to remind myself about the Friends’ belief in “that of God in each of us”. That was what brought me to religion, and I’m trying to hang on to it.

Yes, God in each of us.

For me, having compassion requires an Open Heart that offers forgiveness and unconditional love to everyone, all the time. This personifies the life of Christ. This is a huge and overwhelming task for, in order to practice this with others, I believe that we first need to give it to ourselves. Acknowledging that each us are doing the very best we can, at the moment, with what we have to work with. The corollary to this is that an Open Heart will risk being vulnerable for the sake of others.

Is this lacking in society? Certainly in our Congress and State houses as budgets get balanced on the backs of the poor and marginalized. For sure, but worse than that, it is not apparent enough in our faith communities. Compassion and Open Heart could be our call to action.

Thank you, Donna, for this page. I landed here because a friend told me about Mechthilde’s “The Desert Has Twelve Things”. You have been generous with your time and knowledge, and I have enjoyed reading about these three amazing women. Julian