Jesus set out and went away to the region of Tyre. He entered a house and did not want anyone to know he was there. Yet he could not escape notice, for a woman whose little daughter had an unclean spirit immediately heard about him, and she came and bowed down at his feet. She begged him to caste the demon out of her daughter. He said to her, “Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” But she answered him, “Sir, even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs.” Then he said to her, “For saying that, you may go — the demon has left your daughter.” So she went home, found the child lying on the bed, and the demon gone. Mark 7:24-30

Whenever I hear a story from the gospels, I’ve learned to ask myself:

What does this story tell me about Jesus?

What does it tell me about God?

What does it tell me about the world that Jesus lived in?

In today’s gospel Jesus has traveled beyond the border separating Galilee from the land of the Canaanites. Today there’s a heavily militarized border there between Israel and Lebanon. But there were no borders under the Romans – you could go almost everywhere, because Rome kept an iron grip over every people around the Mediterranean Sea.

But even without borders, there are always walls between people. It seems that we humans have evolved with the need to protect ourselves from “the others” – that is, anyone who is different from us.

And so today we’re still building walls — between peoples, languages, sexes, classes, and religions.

Today’s Gospel shows us this tendency even in the human Jesus: His culture and his Scriptures were telling him that he was called to the people of Israel. He believed that he had been sent to bring the lost sheep of Israel back into the fold.

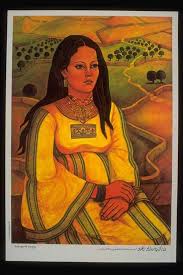

He was probably visiting a Jewish home in Tyre. (It’s still a city in southern Lebanon today, bombed for decades now by Israeli planes and armies.) But into this Jewish home comes a Canaanite woman, begging healing for her daughter.

And now we see Jesus changing his mind – he begins to understand that his call is not only to his own people, but to anyone seeking the love and mercy of God.

Jesus changed his mind? Now the story gets interesting!

Maybe Jesus wasn’t born knowing everything. Maybe he had to learn and grow — just like us — and maybe he, too, had to stretch his mind to see his world as God saw it.

Perhaps Jesus was divine not because he was all-knowing, but because he knew how to open his heart to God. Perhaps, growing up, Jesus had to learn how to listen — and how to be aware of the needs of others.

Perhaps Jesus also had to learn how to pay attention to his own deep feelings, and then to reflect on the meaning of these things. (Perhaps he learned to “ponder these things in his heart”, as the gospel says of his mother Mary).

I think Jesus always yearned to “dwell” – to live and move and have his being –

in that place where God lives. And in learning to “dwell” – listening, feeling, reflecting, praying – he learned to understand where God lives.

But notice, in this Gospel story, that Jesus also found the strength to return to God whenever he found himself off-base, whenever he was wrong, whenever his vision was incomplete.

Can you do that? Can I do that?

Usually I can understand what’s right and what’s wrong, and often I can see where God dwells, but still it’s hard to move myself to that place. Yet that’s what we see Jesus doing in his encounter with the Canaanite woman.

So we look again at this Gospel, and ask:

What can we learn about Jesus? He was a human being who lived and learned,

with a unique ability to stand where God stands.

What can we learn about Jesus’ world (and ours)? We humans have always lived in a world of walls, and even when the walls are breaking down, our first impulse is to build new ones.

What can we learn about God from this Gospel? The God of Jesus Christ builds no walls, but embraces the world.

The early church had to remember the Canaanite woman. They had to remember her because she taught Jesus about the breadth and height and depth of God’s love.

And so, down through the centuries the Canaanite woman has been teaching the church about God’ love, through this Gospel we’ve heard today.

In the 16th century, when the English prayer book was written, the authors still remembered this woman; and you probably remember her prayer, too. We always called it “the Prayer of Humble Access”, but we could have called it “the Prayer of the Canaanite Woman”):

We do not to presume to co:me to this thy Table, O merciful Lord, trusting in our own righteousness, but in thy manifold and great mercies. We are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs under thy Table. But thou art the same Lord whose property is always to have mercy…. BCP p. 337

And in the late 20th century, the poet Brian Wren wrote this hymn, which says it all:

When Christ was lifted from the earth, his arms stretched out above

through every culture, every birth, to draw an answering love.

Still east and west his love extends and always, near or far,

he calls and claims us as his friends, and loves us as we are.

Where generation, class, or race divide us to our shame,

he sees not labels but a face, a person, and a name.

Thus freely loved, though fully known, may I in Christ be free

to welcome and accept his own, as Christ as accepted me. Amen.

To hear the hymn, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_EupYa9VxiQ

Preached at St. Patrick’s Episcopal Church, Kenwood – September 9, 2018.