Christ and the neo-classical worldview

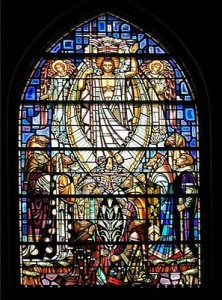

Jesus ascends into Heaven (stained glass, early 20th century)

Christians point to Jesus’ life, death and resurrection as the confirmation that God’s love conquers evil, and that reality is good. In conventional theology Jesus Christ takes the sins of the entire world upon himself. This is very satisfying psychologically, because it releases individuals from the burden of their sins, and it comforts the spiritually afflicted.

So what is wrong with the conventional picture of a Savior who descends from heaven, shows us how to live, forgives our sins, and wins eternal life for us?

The problem is that the conventional picture is no longer believable – and it is also bad theology. The old three-story universe, in which the Savior descended from heaven to earth, is not the universe we live in today. But bad theology also lies behind this picture, because it is a form of ‘Jesusolatry.’

In ‘Jesusolatry’ Jesus does it all; the incarnation occurs just once, in Jesus of Nazareth. The resurrection is also concentrated on Jesus – it is new life given to Jesus, and to us only as we are joined to him. If God is present only in Jesus and if Jesus does it all, then we do not have to meet God in the face of a starving person or in the remains of a clear-cut forest.

Who do you say that I am?

Jesus’ enigmatic question to Peter, “Who do you say that I am?” must be answered differently in every age. Is there an ecological answer?

Prophetic Christologies focus on Jesus’ ministry to the oppressed, and can easily be extended to nature. Today the natural world looks for justice, and prophetic Christologies lead us to extend rights to other life-forms.

Wisdom Christologies understand Jesus as the embodiment of Sophia, God’s creative and organizing energy. From the earliest days of Christianity, the renewal of creation – as well as the salvation of individuals – was seen as part of God’s work in Christ. Wisdom Christologies understand that God is present throughout the creation, wherever justice, care, and respect for others (including nature) occurs.

Sacramental Christologies understand Jesus as God’s incarnation, but also find God’s presence in nature. Sacramental Christology can be very hospitable to ecological concerns. But Jesus’ extraordinary verbal affirmation of the body ( such as this bread is my body, given for you) has not resulted in a tradition that appreciates bodies. And, while sacramental Christologies find God in nature, do they respect nature itself? Or do they use it, however subtly, as a way to God?

Eschatological Christologies speak to one of the most difficult issues for ecological living: giving us hope in the face of despair. Process Christologies affirm the intrinsic worth of all beings, including the natural world. Liberation Christologies recognize the intrinsic connections between human oppression and nature’s oppression.

An ecological Christology

- acknowledges the worth of all life-forms;

- respects the earth and cares for it;

- acknowledges that human salvation and nature’s health are intrinsically connected;

- advocates justice for the oppressed, including nature;

- realizes that solidarity with the oppressed will result in cruciform living for the affluent;

- recognizes that God is with us, embodied not only in Jesus but in all of nature; and,

- through the hope of the resurrection, looks for a renewed creation that includes the entire cosmos.

McFague’s Christology can be summarized by the phrase‘God with us.’ God is with us – we are dealing with the power and love of the universe; God is with us – on our side, desiring justice and health and fulfillment for us; God is with us – all of us, all people and all other life-forms, but especially those who do not have justice, health, and fulfillment.

This is a prophetic Christology: Jesus’ parables, healings, and meals with outcasts are all pertinent to today’s ecological issues. Just as Jesus’ ministry to the oppressed can be extended to the natural world, so can his commandment to love God and neighbor.

And this is a sacramental Christology: Since God cares for, and dwells within, the entire creation, all of nature, not just Jesus, is the sacrament of God. Sacramental Christology also brings hope: the resurrection means the triumph of life over death. (The first Christians saw the resurrection of Christ as the first day of the new creation.) McFague concludes this section with a meditation on a passage from the prophet Ezekiel: “Ezekiel’s valley of the dry bones, one of Scripture’s most haunting and lovely resurrection texts, comes to mind when we reflect on our partnership with God…” In this passage God calls upon two helpers: the human prophet, who brings God’s word to the dry bones; and nature itself – the ‘four winds’ fill the bones with the breath of life. (See Ezekiel 37:1-14)

“In my mind’s eye I see huge mounds of elephant bones, remnants of the ivory trade, the spindly remains of an old-growth forest after a clear-cut, and the visible skeleton of a starving child. Can they also live? Those who trust in the God of creation and re-creation, the God of the resurrection, answer Yes – even these dry bones can live. But, remembering the cruciform reality of Christian life, we must add, only if we, as partners of God, turn from ecological selfishness and live a different abundant life.” (See p. 171)