© Jay Parini. Reproduced by permission of the author.

QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR READING (for October 17):

Jay Parini writes, “Jesus’ ministry became a series of encounters, one-on-one confrontations that changed the lives of those who met him, whether they came to him for healing or instruction. Some brushed against him by accident; yet few didn’t feel the force of their meeting with the Son of Man. Each felt the presence and power of his presence, his intense contact with the kingdom of God, his emotional and intellectual resources, the life-enhancing waters that flowed from him.” (see p. 45)

How do you think Jesus maintained his “intense contact

with the kingdom of God”?

When have you experienced contact with God’s “kingdom”?

What words would you use to describe your experience?

QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR READING (for October 24):

In his Beatitudes, Jesus used the word blessed in a way

that seems completely foreign to our way of thinking.

What did blessed mean to Jesus?

Jay Parini says that the Beatitudes can tell us what kind of man Jesus was.

Read through the Beatitudes again:

What do the Beatitudes tell you about Jesus’ personality?

Each morning of this next week, read one of the Beatitudes, and then reflect on its meaning throughout the day. Each evening, look back over your day for an example of that Beatitude in something that happened — or in someone you met.

1. The poor in spirit

2. Those who mourn

3. The meek

4. Those who hunger and thirst for righteousness

5. The merciful

6. The pure in heart

7. The peacemakers

Jesus said, “I am not your master.

Because you have drunk, you have

become drunk from the babbling stream

which I have measured out.”

– Gospel of Thomas

Here are your waters, and your watering place.

Drink and be whole again beyond confusion.

– Robert Frost, “Directive”

I still have many things to say to you,

but you cannot bear them now.

– John 16:12

WATERING PLACE

After his hair-raising debut at the synagogue in Nazareth, Jesus set out on his public ministry in a determined fashion, walking through Galilee and neighboring provinces. His exact travels vary in the different gospel accounts, but the general directions remain clear, extending out from Capernaum and bordering regions, ending in Jerusalem. From the moment of his baptism, however, he understood and even embraced his fate, although its lineaments emerged gradually.

His ministry became a series of encounters, one-on-one confrontations that changed the lives of those who met him, whether they came to him for healing or instruction. Some brushed against him by accident; yet few didn’t feel the force of their meeting with the Son of Man. Each felt the mystery and power of his presence, his intense contact with the kingdom of God, his emotional and intellectual resources, the life-enhancing waters that flowed from him.

One example will stand in for many. In John’s gospel, he traveled widely on foot from Judea through Samaria, heading back to his base in Galilee, then heading out again. He and his disciples baptized people wherever they went, often going off in pairs to do this work at the behest of Jesus. In Samaria, in a town called Sychar, where Jacob had a well in ancient times, Jesus is seen by himself; exhausted, he sat by this particular well. It was noon when a Samaritan woman stopped to draw water.

“Will you give me a drink?” Jesus asked.(1)

It shocked her that he spoke to her at all, let alone with a request like this one. “You’re a Jew;’ she said. ‘Tm a Samaritan woman. And you ask me for a drink!”

Jews and Samaritans did not associate in those times, and – probably more to the point – a self-respecting Jewish man did not speak to a strange woman at a public place like a well. But Jesus would speak to anyone, wherever and whenever he chose.

The conversation turned progressively more complex, testier, with the stakes increasing as they spoke.(2)

He said to her: “If you had any idea who asked you for a drink, and what God can do actually for you, you would have asked if this man could give you some living water.”

She replied: “Sir, you have nothing to use to draw water, no bucket. This well is very deep. And where can one get this living water you talk about? Don’t tell me you’re more important than Jacob, our father, who gave us this well and drank from it himself, as have his sons and their animals for generations.”

Jesus said, “Those who drink this water will grow thirsty again. But whoever drinks the water I offer won’t thirst again. I provide the waters of eternal life.”

She smiled, wise-cracking. “Please give me this amazing water, so I won’t get thirsty again, and I won’t have to keep coming here to draw water.”

Jesus had her number, however. “Go get your husband. Tell him to come here.”

“I have no husband,” she replied coolly.

“That’s true,” said Jesus. “In fact, you’ve had five husbands, and the man you’re living with at the moment isn’t even your husband.”

Now she was flummoxed, even frightened. How did he know all of this? “Sir, you’re a prophet. I see that now.”

They talked more, and the wheels in her head began to spin. She said, “I know that the Messiah is coming. When he comes, he’ll explain everything to us.”

He responded, “I, the one speaking to you, am he.”

Shocked by this statement, and convinced of its truth, she rushed to tell people in the village about the compelling if rather testy man she had just met at Jacob’s Well.

Like so many of the encounters between Jesus and a stranger, this anecdote layers meaning on meaning. Jesus had been walking for a long time and was “weary” (Greek: kopiao, meaning “beaten down”). In his exhaustion, he stands in for each of us, travelers who stop for refreshment at the hottest time of the day without a bucket but thirsty. In the midst of this crisis comes an opportunity, which is always for Jesus a moment of human exchange and transformation. (He is transformed as much as the person encountered, as he grows into his prophetic role, testing the limits of his own gifts.)

This time, he encounters a double alien: a woman and a Samaritan. Self-respecting men didn’t talk to strange women, especially in these circumstances. But Jesus felt her yearning, her fragility masked by bravado. He always broke down barriers, never erected them. The fact that she was a Samaritan, with “heretical” views, didn’t faze him. As a race, the Samaritans mingled Jewish and Assyrian ancestry, blending so-called heathen practices with traditional Jewish worship. Josephus in his Antiquities calls them “idolaters and hypocrites,” and this view prevailed within orthodox Jewish circles. So Jesus took a risk in speaking with this woman, inviting her to give him a drink.

As ever, Jesus spoke in metaphors, indirectly. The literal image quickly became a symbol here: real water transformed into “living water,” water from a spiritual wellspring. What Jesus offered was a fresh way of looking at the world, a new code of behavior. You talked to women without troubling over gender rules. You confronted people about their past lives, their current situation. You didn’t worry about their racial or political origins but sought to bring them into a state of reconciliation with God, a condition of atonement that would fill them with “living water” that reached beyond physical thirst. Hardly any story in the gospels seems more to the point, more instructive, on such different levels.

GOING OUT FROM CAPERNAUM

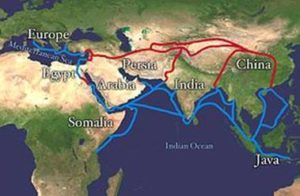

At the start of his ministry, Jesus established a base of operations at the northwestern end of the Sea of Galilee, at Capernaum – a village directly on the Silk Road that marked the last stretch of territory ruled by Herod Antipas. Lower Galilee (the Hebrew word means “circle” or “district”) was known for its great physical beauty: forests and fertile land, the lake itself, and the smooth shoulders of green hills. Light breezes carried whiffs of lavender and thyme to nearby villages. Sheep and cattle grazed in valleys. It was a bountiful place, as Josephus notes, saying that Galilee was “rich in soil and pasturage” and possessed such a “variety of trees” that most residents devoted themselves to agriculture, the easiest way to earn a living there. A distinction should be made, however: Upper Galilee was almost a separate country: hilly, remote, overrun by bandits and political or religious zealots. Lower Galilee, on the other hand, was fertile, abundant. Villages dotted the lower region, which bordered the Sea of Galilee on the east, with the Mediterranean (near what is now Haifa) on the west. It was in this region that Jesus focused his ministry.

The major cities of Sepphoris and Tiberias lay at the southern end of Galilee, and these attracted traders from far and wide. But in the course of his ministry, Jesus seems to have skirted them, preferring a rural ministry and village life.

In Capernaum, Jesus began to gather disciples, enlisting four sturdy fishermen almost at once: Simon (Peter), Andrew, James, and John. (The latter may have been the so-called Beloved Disciple, a mysterious figure mentioned in the gospels but without citing his actual name.) Within a short time he added Philip, Matthew, Nathanael (also called Bartholomew), Thomas, James, Simon the Zealot, Judas (also called Thaddaeus), and Judas Iscariot – twelve in all, in symbolic conjunction with the twelve tribes of Israel. The names vary slightly as they appear in the gospels and this confuses readers. Peter, for instance, was also called Simon – a fairly common Hebrew name. Jesus sometimes referred to him as Kephas, in Aramaic, adding to the confusion. In Greek, his name was Petros (meaning “rock”). Peter – on whom Jesus by tradition had built his church – was a married man. (We know this because he had a mother-in-law whom Jesus healed when he found her in bed with a fever.) Probably most of the disciples lived in or around Capernaum, and one can only imagine what private dramas may have taken place within their households as they tried to explain to their families that they planned to drop everything and follow Jesus.

Mary Magdalene entered the picture early. She was not among the twelve disciples but played a huge role in his ministry; she was there at the foot of the cross and was, crucially, the first person to see him after his resurrection, as recorded in both Mark and John. She was (by tradition) the author of the apocryphal Gospel of Mary, discovered in 1896 but probably dating from the second century. One should also note a line from the Pistis Sophia – a significant Gnostic text also dating from the second century – where Jesus says that Mary Magdalene would “tower over all my disciples.” That Jesus enormously valued her company cannot be doubted, though the idea that Mary Magdalene was more than a very dear friend remains a point of speculation.

Although unmarried, Jesus liked being around women, and made a point of including them in his company. A good picture of what his ministry looked like appears in Luke 8:1-3: “Soon afterwards he went on through cities and villages, proclaiming and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God. The twelve were with him, as well as some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had been cast out, and Joanna, the wife of Herod’s steward Chuza, and Susanna, and many others.” Women followed him eagerly, and many became leaders in the early Christian church. It was much later – many decades after his death – that misogyny took root in the church, making it awkward for women to assume leadership roles. But Jesus himself never shied away from women, nor did he discourage them from assuming spiritual authority in his name.

The twelve disciples remain fairly indistinct, though we pick up tidbits of individuality here and there. There were two pairs of brothers: Peter and Andrew, James and John. Philip was born in Bethsaida, the home of Andrew and Peter, and he appears to have spoken Greek (instead of Aramaic), so he later traveled to Greece, Phrygia, and Syria to convert the gentiles in their familiar tongue. Simon the Zealot was sometimes called Simon the Cananaean (or Canaanite), and one assumes he had strong political views, given his membership in the revolutionary Zealots. His presence reminds us that, however spiritual the kingdom of God might be, there was a political element in play, and Jesus acknowledged this by including Simon among his twelve. On quite another note, Matthew was a tax collector – a disreputable occupation among Jews, who loathed the Roman authorities – and he may be the one called Levi in Mark. By allowing a tax collector among his closest followers, Jesus showed everyone he met that he took no obvious political side in the struggles between Roman rule and its client kings in Palestine. Thaddaeus was also called Judas, but he was not the Judas who betrayed Jesus in the final days. That was Judas Iscariot – a creature of legend, much of it post-biblical. We learn in Acts 1:26 that to replace Judas, “the lot fell upon Matthias.” This way, the number could remain twelve. But Matthias remains a bit of a mystery, lost in the pages of history.

Modern archaeologists have added a good deal to our sense of the historical reality behind the ministry of Jesus. They found, for instance, the remains of an ancient synagogue in Capernaum – possibly the exact spot where Jesus taught. When he took up preaching there, the people listened keenly and “were astounded by his teaching, because his words had authority” (Luke 4:32). He taught them that the kingdom of God lay at hand, even within them, and urged them to open their hearts and minds to the spiritual realities he had himself experienced, inviting them to drink from the living waters.

One of his earliest acts – a public demonstration of his unusual gifts – was to cast out a demon from a severely deranged man, an exorcism that startled the village where the man had lived. Later, he cured Peter’s mother-in-law of a fever, and news spread quickly about this wonder-working healer who had fetched up in Capernaum to perform amazing feats. Crowds gathered at sunset outside of Peter’s house, where those with “various kinds of sickness” surrounded Jesus, who healed them one by one, ever patient, always listening as much as speaking.

Jesus also spent time instructing the twelve in Capernaum, making sure they understood his ideas before they took his ministry on the road. At one point, he gathered a child into his arms and declared: “Whoever receives one child in my name receives me.” The message came through loudly: Don’t let your ego get in the way of your goal, which is to spread the good news of the kingdom. And remember that it’s not a complicated message, as any child can receive it. Go with your heart, not your head.

The story of Jesus as healer and exorcist has a peculiar ring today. But in Palestine twenty centuries ago, healers and exorcists roamed the landscape, many of them quite gifted. In truth, nobody in the gospels seems to have doubted that Jesus performed miracles of healing or cast out demons; it was only a question of in whose name he performed these mighty acts.(3) To me, it’s not surprising in the least that Jesus could empower those with physical ailments or “demons” to recover: faith is a tonic, and Jesus asked those he healed to put their trust not in himself but in God.

Great men in the ancient world were often thought to perform miracles. Philo, a major Jewish writer and contemporary of Jesus, writes that the Emperor Augustus was an “averter of evil” who quieted storms and stopped plagues, and nobody questioned this assumption. People thought that the Emperor Nero had quelled a storm, too.(4) Indeed, the kinds of miracles that Jesus performed suited an age before the advent of psychoanalysis or antidepressants. He had a surprising talent for opening up the victims of madness to healing energies, and this doesn’t sound especially “supernatural” to me. It may require a stretch to imagine he could make a blind man see or a victim of paralysis walk; but I have no doubt that faith can boost one’s immune system and that its emotional balm has healing effects. Most of the other miracles in the gospels, such as walking on water or quelling storms or turning water into wine, strike me as intensely symbolic acts and should be considered as such. This doesn’t mean they should not be considered true as well. It means that the writers of the gospels had a different view of truth from that held by modern philosophers and historians who, in Oscar Wilde’s sublime phrase, are “always degrading truths into facts.”(5)

The gospels offer tantalizing glimpses of the public ministry of Jesus, repeating things he said in slightly altered form – not a surprising thing, given that Matthew and Luke appropriated much of Mark. Plagiarism was not a problem in those days, and one assumes in any case that Jesus repeated himself: all teachers do. He honed his message on the stump, finding the right emphases, the best rhetorical structures for making his points. This must have been a superb time for him and his disciples, who reveled in his presence, consumed by his fiery nature, his wit and wisdom, his superb knowledge of Hebrew scripture, his sense of God’s presence working in his life and potentially transforming theirs as well as they shifted from village to village, often sleeping outside under the stars, bypassing towns and cities by going through the countryside, where they slept in fields or barns. Needless to say, both the Roman and Jewish authorities looked warily on this itinerant band, who seemed oblivious at times to laws and customs.

One gets a hint of the immediate problem in Mark 2:23-28, where Jesus and his followers “went through the fields of grain” near a village “on the Sabbath day.” As they walked, the disciples of Jesus blithely plucked “corn” (probably barley) at random. This annoyed the local Pharisees, who followed Sabbath laws with fanatical rigidity, assuming that the way into God’s kingdom involved adherence to specific codes. You simply didn’t reap on the Sabbath, even if you need food. The Pharisees – as strict followers of Mosaic law – complained to Jesus, who explained that King David himself had gone into the high priest’s house once and taken the “show bread,” which only priests could eat with impunity; he gave this bread to his hungry followers. And why not? David was a king, after all, and it was good to be king.

Jesus’s lackadaisical response to Jewish law shocked and annoyed the Pharisees. Who did he think he was? Was this young man from a poor family in Nazareth claiming to be a royal personage, even David reborn? Did he have any idea how scandalous he sounded? Jesus listened to them respectfully but rebuffed their legalistic thinking: “The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath: Therefore the Son of Man should also be considered Lord also of the Sabbath.”(6) One can only imagine their response.

One tracks Jesus in his daily ministry in different ways in the four gospels, and it’s impossible to get a clear route or sense of chronology. Yet a kind of summary of his work appears in Matthew 4:23-25: “And Jesus walked about Galilee, teaching in the synagogues, preaching the gospel of the kingdom, and healing every kind of sickness and disease among the people. And his fame spread even throughout Syria: and they brought unto him sick people that were taken with different illnesses and torments, and those who were possessed with devils, and those that were mad, and those that had forms of paralysis and palsy; and he healed them. And vast multitudes followed him from Galilee, and from Decapolis, and from Jerusalem, and from Judaea, and from beyond the Jordan.” Although glimpses of him occur in various parts of Palestine, he confined himself to Galilee and its shorelines for the most part, with a final journey to Jerusalem through Judea and Perea.

The exact length of his ministry remains unknown, though he apparently began preaching and teaching when he was “about thirty years old” (Luke 3:23). The events described in Mark could easily have taken place within a single year or less, even a few months, and this is true of Matthew and Luke as well. Only one Passover celebration is mentioned in the Synoptic Gospels, hence the assumption that the ministry occupied him for a year or so. In John, however, three Passovers occurred in the course of the public ministry, which suggests to many readers that three years must have elapsed. But the gospels’ narratives follow no timeline, and events in the story occur in a different order in each version, and the lapse of time is impossible to gauge. Not being biography in the modern sense of that term, the gospels should be taken as impressionistic accounts of an extraordinary life, and the authors (probably many authors, who expanded and modified earlier texts) shift the scene of the action from one place to another almost at will to illustrate the sort of things that Jesus did, often gathering the specific teachings of Jesus into neat summaries – not unlike the helter-skelter way in which they would have been presented in real time.

Matthew, in particular, arranged the teachings in well-defined sections. This gospel may actually have been a textbook, written in Antioch for an audience of students at what might have been a very early Christian seminary of sorts.(7) It puts forward a tidy compilation of sayings and parables, laid out in didactic fashion. At the core of this teaching lies the Sermon on the Mount, which draws on vast reservoirs of desert wisdom, looking to the East as well as the West for inspiration and ideas. If it were the only record of Jesus that survived, it would suffice to place him among the handful of major spiritual and ethical guides in history.

THE SERMON ON THE MOUNT

The Sermon on the Mount begins with a series of statements known as the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3-12). These aphorisms reach far beyond the ethics of traditional Judaism, appropriating a version of the Hindu and Buddhist idea of Karma, which suggests that what happens to us is rooted in our deeds: If we show mercy, we receive mercy, for instance; if we behave violently, violence will define us. This is called the Karmic cycle, and it became a pervasive and grounding concept in Eastern religions. Of course, Jesus framed the concept in ways unique to himself and developed in later Christian doctrine, as in Galatians 6:7: “Whatever a man sows, that shall he reap.”

The Beatitudes follow in the King James Version, as the text is so familiar:

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness:

for they shall be filled.

Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.

Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake:

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you,

and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

Rejoice, and be exceeding glad: for great is your reward in heaven:

for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.

It was Pope Benedict XVI who said in his excellent study of the life of Jesus that anyone who reads the Sermon on the Mount attentively must realize that the Beatitudes present “a sort of veiled interior biography of Jesus, a kind of portrait of his figure.”(8) We can deduce what kind of man he was from things he advocated in this sequence of statements centered on his dream of a fully realized kingdom. Each of the Beatitudes refers to this kingdom, which is already within reach of those who listen. That Jesus should begin with the “poor in spirit” matters hugely, and it embodies the most radical turn in his teaching.

READING THE BEATITUDES

“Blessed are the poor in spirit.”

It’s an appealing start, but who exactly are “the poor in spirit:’ and how do they relate to the poor in the usual sense, those without worldly goods? (In Luke, the opening Beatitude omits “in spirit,” confusing the matter and opening a good deal of debate.) Jesus refers to an understanding of the poor as pictured in Isaiah, where “poor” refers to those with a humble demeanor. He praises this humility, which may connect to physical poverty (as it clearly does in Isaiah 58:7, where the poor are those without bread), or those requiring sustenance for their spirits. The message here seems broader, however: the humble will be blessed (Greek: makarios, usually translated as “blessed,” also means “joyful” as well as “favored” or “happy”), and they will come into a kingdom that exists beyond time and space.

As the poor in spirit often dwelled in material poverty, the correlation between those literally and figuratively poor would not have been lost on those who listened to Jesus. The people of Palestine were hardly wealthy, and the crowds who gathered before Jesus experienced rural poverty of a grueling sort, threatened each day by hunger and disease, discouragement and fear of violence. That Jesus should speak to them, especially in the first of his Beatitudes, must have been heartening. They had a special place in God’s kingdom.

There’s an old Jewish story that goes like this: A rabbi is asked why nobody sees the face of God anymore, as they did in ancient times. The rabbi says ruefully that it’s because nobody these days can stoop so low.(9) In many ways this is what Jesus means in this first Beatitude: Stoop! Find your blessings in those who lack power, wealth, or resources. Prefer humility to arrogance. This is the way to happiness, to a blessed state. (10)

“Blessed are they that mourn.”

Jesus understood that life is suffering – one of the four “Noble Truths” espoused by the Buddha. (11) Jesus singles out those in special anguish, such as those who mourn the death of a loved one, the anguish of a relative or friend, the pain of illness or mental despair. For anyone, it’s only a matter of time before anguish descends. As the poet Robert Hass has written: ”All the new thinking is about loss.” But so is all the ancient thinking. As this Beatitude suggests, in the midst of losses, God offers comfort. In fact, in times of great personal difficulty, spiritual progress becomes possible. Ever conscious of the Jewish scriptures, Jesus recalls here Ecclesiastes 7:3, where we read: “Sorrow is better than laughter: for by the sadness of the countenance the heart is made better.”

“Blessed are the meek.”

Who are these people, the meek, who will “inherit the earth,” which is quite a grand reward for their behavior? We don’t usually like the meek, and the word in English has unpleasant connotations: the meek are timid, frightened, even foolish. They tug their forelocks and bow to those who are stronger. But this isn’t what the Greek word (praeis) actually suggests. Aristotle uses this word to mean somebody who understands the golden mean, who picks a way between anger on the one hand and subservience on the other. (12) Another translation of the Greek word is “nonviolent” or “peaceful.” Further, the term correlates to a word associated in Hebrew scripture with Moses: “Now the man Moses was very meek, above all the men which were upon the face of the earth” (Numbers 12:3). One doesn’t usually think of Moses, a great Israelite leader, as “meek.” But the word obviously has many levels of association.

In this Beatitude, Jesus alludes specifically to a famous Hebrew text, Psalm 37:11, which reads: “But the meek shall inherit the earth; and shall delight themselves in the abundance of peace” (KJV). Those who will inherit the earth will not be aggressive or self-aggrandizing. They will be “meek,” in the fullest sense of that term, nourished through its Hebrew and Greek roots.

“Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness.”

The message turns on two verbs: to hunger and to thirst, words that in the context of Middle Eastern life in the first century must have carried a special vividness. Here physical needs stand in for spiritual realities. The blessed ones reach for dikaiosune or “righteousness,” for a condition that, in Greek, suggests a yearning for oneness with God, a conjunction of wills. “It does not mean the ethical quality of a person,” cautions Bultmann. “It does not mean any quality at all, but a relationship.” (13) The relationship in question is between God and the seeker, and it has to do with the seeker’s actions as well, in which he or she aspires to accept and understand the will of God. And Jesus would have had in mind a passage from Isaiah 32:17: “And the work of righteousness shall be peace; and the effect of righteousness quietness and assurance forever” (KJV). The righteous shall “be filled,” their hunger and thirst “satisfied” as they come into the kingdom of God.

“Blessed are the merciful.”

Here is an obvious reference to the Karmic cycle, as noted above. And Jesus himself showed mercy repeatedly as he moved from village to village, as when he met a blind beggar by the road (Luke 18:38) and the beggar called to him: “Jesus, son of David, have mercy on me.” Jesus restored his sight at once. This willingness to act, to respond to those who ask for help, occupies the core of Christian ethics. It can’t be overstated: the essential Christian urge is toward forgiveness. It should displace feelings of anger, hate, resentment, and revenge. This is a transformation that, in my view, occurs naturally as one takes up the cross of Jesus and follows him. There is no time for revenge. One looks around and sees everywhere such need, and resolves to act, in political ways or simply personal ways, offering help to those who require counsel, friendship, food, or shelter. The natural consequence of such “mercy,” of course, is forgiveness, the ultimate gift of the spirit, as it provides a conduit to atonement or union with God.

“Blessed are the pure in heart.”

Purity of heart belongs to those who behave without mixed motives, who live in accord with God’s will, and who therefore apprehend this purity Jesus asks for. The point is amplified memorably in Titus 1:15: “To the pure all things are pure: but to those who are defiled and unbelieving, nothing is pure; even their minds and conscience are defiled.” This Beatitude follows naturally from being humble and “meek,” from giving to others, from listening to Jesus when he tells us to “love one another” as he loved us. But it suggests as well that the very act of striving for purity activates a vision of God: in becoming pure, we become Godlike, merging with the Spirit. We “seek his face,” as Psalm 105 urges us to do, and we find it: the face of God that, as St. Augustine once suggested, we discover in the human visage of Jesus.

“Blessed are the peacemakers.”

Jesus blesses those who promote peace among their friends and neighbors, saying they will become the “children of God.” And by extension, he blesses those who promote peace at large, These are the happy ones, the true inheritors of the kingdom; being filled with peace, they spread peacefulness around them. The peacemakers must always step forward, urging caution in situations where war or conflict arises. In an age dominated by horrendous violence and wars, these words by Jesus must have sounded a loud gong. Again, a Karmic truth emerges in this Beatitude: making peace leads to peacefulness, which ultimately defines the kingdom of God as a state of true reconciliation with the Creator. The true children of God understand that their peacefulness is a gift to the world at large.

“Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake.”

This final Beatitude would have pricked the ears of his disciples, each of whom would suffer martyrdom by the end of his life. The evangelist here, writing in a time of political stress for Jews after the fall of the Second Temple in 70 CE, would also have caught the attention of severely persecuted and threatened Christians.(14) His promise to them was the ultimate boon: the kingdom of heaven, in all its dimensions, implying a kind of restoration as alienated human beings unite with the ground of their being, no longer “outside” of eternity but satisfied, complete, entering a “world without end,” as we read in Ephesians 3:21. As always, righteousness means rightness with God, oneness, a convergence of the human and divine will, as seen fully within the person of Jesus himself.

READING THE ANTITHESES

The Beatitudes form only the first part of the Sermon on the Mount, which occupies three long chapters in Matthew. What follows directly is often called the Antitheses – six statements that adhere to a rhetorical form that would have sounded familiar to readers schooled in classical rhetoric: “You have heard it said that … but I tell you this.” They amplify Mosaic laws in significant ways. I paraphrase them in what follows, with a brief comment on each:

1. You have heard it said, Do not kill. I say this: Don’t even be angry.

Jesus lost his temper at times, so one may well ask if he was hypocritical. On this, he might have agreed with Ralph Waldo Emerson, who said: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Jesus had a large mind and heart, and he entertained many weathers of feeling – like any human being. Yet he clearly hated injustice, poverty, and cruelty of any kind. He also understood that anger isn’t a useful response, as it will eat away at the soul. Again, the idea of Karma presides, however Christianized by Jesus: anger leads to murderous behavior. Forgiveness leads to godly behavior. So he takes his listeners back to the origins of murder, anger itself.

2. You have heard it said, Don’t commit adultery. I will go further: Don’t even lust after someone in your heart.

The strictness here seems, in today’s erotically-charged world, to pose an impossible ideal. How can one possibly not lust after somebody in one’s heart? Do we control this? Jesus was of his time, and this ideal may seem far too much to ask. But it underscores a message that still has relevance. Our lives are happier without insane lust, as Shakespeare suggests in Sonnet 129, where he writes, “The expense of spirit in a waste of shame / Is lust in action.” Shakespeare meditates on lust in its various forms: past, present, and future. In each case, it roils the human spirit, producing shame, unease, blame, and myriad other distresses. It rarely helps in the pursuit of fidelity, which is where (in the Christian view) happiness lies. As Wendell Berry, the poet, has said: “What marriage offers – and what fidelity is meant to protect – is the possibility of moments when what we have chosen and what we desire are the same.” (15) Jesus locates the Karmic origins of adultery in lust. It’s a cycle that can only be broken at the beginning. That might seem like an impossible task; but the beginning is always coming around again, so hope lies there.

3. You have heard it said, If you wish to divorce your wife, serve her divorce papers. I say this: The only way you can leave your wife is if she is unfaithful.

The message is clear: fidelity lies at the heart of love. You can leave someone only if he or she has already left you. And yet Jesus builds here on the previous antithesis, where he suggests (to me) that fidelity lies at the heart of both marriage and community. And only within a community of faithful people is one actually free. Sexuality is sacramental, and when taken out of this context, it leads to exploitation. Respect, sexual discipline, and fidelity lead to the practice of love, and this is something worth practicing. And yet, as Wendell Berry further writes, “the idea of fidelity is perverted beyond redemption by understanding it as a grim, literal duty enforced only by will power.” (16) It’s not about forcing the issue, settling into a joyless relationship. Fidelity and love move into the same space naturally, blossoming in the good soil of a respectful relationship.

4. You have heard it said, Don’t break an oath. I tell you this: Don’t make promises or oaths in the first place if you’re in danger of breaking them. Say yes or no, and don’t hedge.

Whatever you say, you should mean it. Be clear. Jesus calls for sincerity and transparency in making promises or commitments to others. Here he asks for fidelity of the tongue as well as the body and soul. Again, faithful speech leads to good faith. Our words must become deeds. (John P. Meier, in a long chapter on what is called the “prohibition of oaths” in the fourth volume of A Marginal Jew, makes the sensible point that the more severe teachings of Jesus – that one should not make oaths or promises, that one should not divorce one’s spouse – are further examples of Jesus as “the eschatological prophet proclaiming the rules of conduct binding on those who already live” inside the kingdom of God.(17)

5. You have heard it said, An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. But I tell you this: If somebody strikes you, turn the other check. If someone demands your jacket, give it to him and your cloak as well.

This remains a core teaching of Jesus and, perhaps, his most radical revision of Judaic morality, upturning the apple cart. Resist evil but do so without violence is a strong message, one that influenced Tolstoy, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King. But it’s a complicated matter, one that has vexed Christians throughout modern history. Political leaders who supposedly follow the Way of Jesus have rarely taken his teachings on the matter of passive resistance to evil with anything like the seriousness they require. Jesus’s approach sounds too radical, a bit frightening. As human beings, our natural tendency is to strike back in self-defense if not anger. Jesus cuts against the grain, as ever, asking us to respond to evil not passively but actively, showering love and good will on those who hate us, who do us harm. He asks for restraint and much more. He asks for insane generosity: give it away, especially if you love it. Cast your bread upon the waters.

6. You have heard it said, Love your friends but hate your enemies. But I say this: Love your enemies. Do good to those who try to harm you.

This behavior represents an extension of the previous antitheses. It’s an ideal, and it suggests another way to break the Karmic cycle of hatred by allowing love to flow toward even those who fall into the category of “enemies.” In a sense, this love – modeled by Jesus in his life and deeds, especially in going to the cross – dissolves hatred. It’s a potent instrument that makes change possible. As before, Jesus builds idea on idea, amplifying and extending his thoughts. It seems unnatural to do good to those who try to harm us; but it’s the Christian way, offering an alternative to the violent response that often comes more naturally when we feel attacked.

These six antitheses take seriously the command to love. In various ways Jesus suggests that we can break cycles of violence and hatred, that the possibility of change lies before us, within our grasp. He takes every consequence back to the actions that produced it, for either good or evil, urging us to undergo a change of heart. Yet he understood that we can’t simply do this hard work of transformation by ourselves. Change requires God’s intervention in our lives, an overflowing of the Spirit into human consciousness. Only by the grace of God can we begin to effect change, to participate in the gradually realizing kingdom that lies within us, however difficult of access. This is not a matter of willing ourselves to perfection; it’s about letting the will of God enter our lives, so that his will becomes ours: a very different dynamic.

Aware that we must seek God’s help in our shift of consciousness, Jesus offered an example of prayer, a bid for grace that he asked his disciples to emulate, making prayer and meditation a central part of their spiritual practice.

THE LORD’S PRAYER

The Lord’s Prayer occupies a central place in the Sermon on the Mount, as it should. It invites us to acknowledge our imperfections, our helplessness, framing a wish for the kingdom of God to come as quickly as possible.

With a single gesture, Jesus put prayer at the center of the Christian life, and some of the most vivid scenes in the gospels occur when Jesus goes off by himself to pray, as he does in the desert or, during his final week, in the Garden of Gethsemane. Prayer was, for him, a way of opening himself to God-consciousness. It was, as prayer must be, a way of listening, allowing a kind of holy silence to fill the mind’s honeycomb. A prayer is a bid (the Anglo-Saxon word for prayer is bed, and the German word is beten, in Dutch, bidden), a bid for grace, for communication with the Spirit, an invitation to be filled with God’s love. We speak to God in prayer as well as listen; but we require words, as Jesus knew, which is why he put forward this example in Matthew 6:9-14: (18)

Our Father, which art in heaven,

Hallowed be thy name.

Thy kingdom come,

Thy will be done in earth,

As it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our trespasses,

As we forgive them that trespass against us.

And lead us not into temptation,

But deliver us .from evil.

For thine is the kingdom,

The power, and the glory,

For ever and ever.

Two versions of this prayer exist, in Matthew and Luke, and not all manuscripts of Matthew add the doxology (the last three lines).(19) But the character of the prayer is consistent in both versions. One begins by praising God, regarding him as a father – a traditional Jewish idea, as when God speaks in Exodus 4:22: “Israel is my son, even my firstborn.” But Jesus urged us to make a personal connection with God, as in a father-child relationship. Every phrase in the Lord’s Prayer resonates with the Jewish scriptures, emerging from earlier concepts but always expanding, modifying, shifting as Jesus offered his followers a New Covenant.(20)

The other elements of the prayer fall easily into place. We invite God’s kingdom to arrive sooner rather than later. God’s will (not ours) controls our aspirations, so it’s no use forcing the matter, trying to grit our teeth and white-knuckle our way to perfection. We ask for “daily bread” (21) – referring here to spiritual sustenance as well as food. In keeping with what was already put forward in the Beatitudes and Antitheses, Jesus suggests that we must forgive those who do us ill while asking forgiveness for our own foolish, ill-considered, cruel, selfish, and thoughtless deeds. Penitence lies at the heart of this prayer. We must ask for forgiveness, as we inevitably fall into error, stepping off the path. We wish to be delivered from evil (in Greek, the evil one: ho poneros-a version of the Hebrew Ha-satan). Evil is everywhere around us, and we hope that God will keep us from its path. The doxology in the last three lines offers more praise to God. So the prayer begins and ends with praise. It’s a wonderfully focused petition, a way to share in the prayer life of Jesus by following his example.

The immediate focus of “Thy kingdom come” – on the emerging kingdom of God – needs elaboration. The problem of exactly when Jesus thought the kingdom would arrive or what form it might take has vexed New Testament scholars, especially after Johannes Weiss (1863-1914), a major German theologian, put forward his theory of Jesus as a prophet obsessed with the idea of the coming “end times” or eschaton. And the Book of Revelation – as a conclusion to the New Testament – has not helped matters, offering a fevered vision of the final days, though it almost certainly refers to things happening at the time it was composed, not a vision of some dire end-of-the-world scenario, as Elaine Pagels has argued.(22) Indeed, it might better have been called Apocalypse Now.

The Lord’s Prayer is gentler than anything in the Book of Revelation. It encourages a penitential attitude, so that the full benefits of prayer (which include reconciliation with God) can be experienced. This bid for grace is easily repeatable, like a mantra – as when Christians “pray the Rosary,” moving from bead to bead on a necklace – where it often forms a part of a spiritual exercise.(23) This is the only time in the New Testament where we get any sense of how Jesus actually sounded when he prayed, and we put ourselves in his shoes by repeating these words, which engender strong emotions and open the heart to divine consciousness. We become, in the course of saying the Lord’s Prayer, like Jesus himself.

CONSIDER THE LILIES

While the Lord’s Prayer occupies the center of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus follows it with a number of important sayings and exhortations as well as parables. The sixth chapter of Matthew moves toward a lovely passage, beautifully rendered by the King James translators:

Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment? Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they? Which of you by taking thought can add one cubit unto his stature? And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil nor, neither do they spin: And yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.

As an antidote to worry, Jesus suggested that we “consider the lilies.” Faith bestows ease, confidence, and emotional balance. And here lies the reward of following the Way of Jesus: we can’t add anything to our stature that God hasn’t already given, by his grace. To a degree, this teaching of Jesus once again parallels a key Buddhist idea, that the universe will take care of us. We have only to observe the present world, pay full attention to its details, and its meanings will reveal themselves: “For the heavens declare the glory of God” (Psalm 19: 1).

THE GOLDEN RULE

A diamond glitters in Matthew 7:12: “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets” (KJV). Since the Middle Ages, this piece of ancient wisdom has been called the Golden Rule.(24) It’s also known, less poetically, as the ethic of reciprocity, and versions of this idea occur in most world religions, including Hinduism and Buddhism. In the Analects of Confucius (XV.2.4) another framing of this thought appears: “Do not impose on others what you yourself do not desire.”(25) Similar statements go back as far as the Code of Hammurabi – probably the oldest written statement of this principle, dating from around 1780 BCE.(26) A version also appears in the sayings of Rabbi Hillel, a major religious leader at the time of Jesus, who delivered what is often called the Silver Rule. Hillel asks people to refrain from doing anything to others that would feel distasteful to them personally. Jesus could easily have heard this teaching from Hillel or his followers. He might have picked up versions of this idea as he talked with merchants or travelers on the Silk Road in his youth. In any case, it doesn’t matter where Jesus got the idea: it was already in the air. And he improved upon it, making it central to his teaching.

FINAL WISDOM IN THE SERMON

The Sermon on the Mount ends with a blizzard of aphorisms that act as a summary of the whole, as in the following selection (KJV):

Judge not, that ye be not judged.

Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find.

Ye shall know them by their fruits.

It’s worth recalling that aphorisms or sayings are not parables, which remain central to both the content and form of Christian teaching. A parable is a brief, indirect story with a moral; it may, like a Zen koan, provide a puzzle that needs solving – or have a point that sneaks up on the listener. The Sermon ends with a good example of the form, the parable of the two houses, which instructs the reader on how to interpret and use the sayings of Jesus:

Therefore whoever hears these sayings of mine, and obeys them, I consider him a wise man who built his house upon a rock: And the rain came down, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and yet it didn’t fall because it was founded on a rock. And everyone who hears these sayings of mine, and doesn’t obey them, shall be considered a foolish man who has built his house upon the sand. And the rain came down, and the floods arrived, and the winds blew and beat upon that house, and it fell: and the fall of it was great.

It was a deft move in this parable to end with a metaphor of two houses, one built on sand and therefore unstable, and one built on solid rock. It’s not a difficult parable, as anyone can comprehend the metaphor. Sigmund Freud once said that whenever people dream of a house, they dream of their own soul. Jesus intuited this, and his two houses are human souls, one of which has a foundation provided by Jesus – a rock-like sense of the human condition enhanced by his teaching. Souls in communication with God should fear no storm, no dislodgment. The wind and the rain will fail to topple (although they might shake) such people. But those with souls built on sand will find it difficult to weather out a storm.

THE PARABLES

Wherever he went, Jesus spoke in parables, and these – in the Synoptic Gospels especially – form the marrow of his teaching. In using parables, Jesus harks back to Hebrew scripture, which provides an array of Jewish parables (Hebrew: mashal). In Ezekiel one finds short, pithy statements or aphorisms – a genre that Jesus loved – as well as longer allegorical stories with a twist or moral at the end, the main form of parable that Jesus adapted for his purposes. That they often seem to possess a secret at their core may puzzle some, but the origins of the parable lie in the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible, and it wasn’t foolish to disguise messages in ways that made them less accessible to the larger world, especially during times of exile or political turmoil.

Ezekiel, for instance, was written during the Babylonian exile, when Jews found themselves in a foreign land, at a loss to understand their state. Solomon’s Temple had been thoroughly destroyed, and narratives that prophesied the triumph of Israel seemed hopelessly at odds with developments on the ground.(27) The nation of Israel had been uprooted: physically and spiritually. The plot of their story had been rudely disrupted. So the author of Ezekiel and other writings sought a hidden narrative, a buried design that might be grasped in the form of parable. In The Parables in the Gospels (1985), John Drury says: “The element of secret knowledge which had always been part of the structure of prophecy came to dominate it. The prophet became a wise man, a dreamer and visionary, an interpreter of dreams like Joseph in his affliction and exile. As such he held the clue.”(28)

The parables in the gospels function in a similar way, offering oblique teachings, almost preternaturally evasive in certain instances. In Mark 4:13, for example, Jesus says (perhaps with a slight grin): “You don’t know this parable? So how will you know all the parables?” The parable here concerns the sower who sowed his seeds in stony ground. The birds came and ate the seeds; other seeds fell on “good ground,” and they yielded fruit in abundance. In the middle of the telling Jesus says: “To you has been given the secret of the kingdom of God, but for those outside everything is in parables.” There is a lot of mystification, as Jesus goes on to say that the parables make sense only to those who hear them with the ears of faith; those on the outside can’t understand what they hear. Mark observes that Jesus spoke in parables to the people at large, “and when they were alone, he expounded all things to his disciples” (Mark 4:34). Jesus didn’t want the people at large to understand his words too easily, “lest at any time they should be converted, and their sins should be forgiven them.”

Readers may object: Doesn’t Jesus actually want his followers to be forgiven? This verse – like so many verses in scriptural writing – needs context for understanding. Mark actually quotes a passage from Isaiah (6:9-10), where God tells his prophet to say to the people: ”And he said, Go, and tell this people, Hear ye indeed, but understand not; and see ye indeed, but perceive not. Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their heart, and convert, and be healed.” Keeping this passage from Isaiah in mind, one begins to see this puzzling remark of Jesus as yet another attempt by the evangelist to place him, perhaps clumsily in this instance, in the tradition of Jewish prophecy. Mark assumes incomprehension, that the audience at hand will hear Jesus but not understand his words. They will not accidentally “turn and be healed,” as their turning would be an intentional act. One must, however, assent in order to understand.

The continuously pressured, anxiety-filled historical context of Jews under Roman rule freights the parables of Jesus. They generate multiple layers of meaning as Jesus attempted to communicate with people who might resist what he had to tell them, as with the infamous saying that it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter heaven.(29) Here, as elsewhere, Jesus wished to annoy, even outrage, the elite classes, especially those who understood only too well that this upstart crow sought to overturn aspects of Jewish law, despite his protest to the contrary in the Sermon on the Mount. His new covenant posed a threat to the old one, making those who listened nervous. If they dropped everything and followed Jesus, anything might happen.

Jesus spoke fearlessly, unafraid to challenge or upset those who listened. One senses that edge in his parables, a cunning that threatens to undermine established opinion and overturn expectations. He shocked his listeners into fresh understandings, as in the parable of the mustard seed, which appears in all three Synoptic Gospels. In Mark 4:30-31, it runs as follows:

What’s a suitable image for God’s kingdom? What parable might I use to explain it? Think of a mustard seed. When scattered on the ground, it’s the smallest of all the seeds; but when it’s planted, it grows and becomes the largest of plants. It puts out such extensive branches that the birds in the sky can nest in its shade.

In other words, something quite massive can grow from something as tiny as a mustard seed. (The revolt of one person can lead to large political movements, for example. A single spiritual awakening can precipitate a wave of religious feeling.) The plant in this parable would be the black mustard, which grows to nine feet in height. Jews rarely planted these in their gardens, regarding them as weeds; but one found them abundantly in the fields. The idea of a tree filled with birds suggests that the kingdom of God would in due course welcome all comers, and that it would grow to a considerable size. Although it grew wild, it flourished under circumstances of cultivation. And it had many health-giving properties. This parable works on a political level: one can imagine Christians establishing a righteous kingdom on earth; it also works on a spiritual level, as the consciousness of the individual Christian deepens into a faith-based community, and one begins to comprehend that Jesus is the vine and we are its branches.

Drury writes of this parable: “Here is an image of the eschatological state or kingdom, a tree full of birds. Eschatology, of a decidedly futuristic sort, as we would expect in the context, triumphs and has the last parabolic word before the editorial conclusion.”(30) That “editorial conclusion” follows in the next verse: “With many such parables he spoke the word to them, as they were able to hear it.” Drury and many other scholars go to considerable efforts to locate each parable within the developing context of the specific gospel (as well as within the unfolding life of Jesus) and its specific historical setting.(31)

The parables deal with ordinary things, such as baking bread (the Parable of the Leaven) or knocking on a neighbor’s door (the Parable of the Friend at Night) or with a mugging by the roadside (the Good Samaritan). In each case, Jesus wished to teach a lesson, make a point about the kingdom of God, or nudge his followers in a more enlightened direction. But it was easier to communicate with familiar imagery – often drawn from rural or village life. As ever, he met people where they were, in their own daily lives.

A fair number of the best parables concern loss and redemption, as in Luke, where three parables on this theme occur: the parables of the Lost Sheep (the shepherd goes out of his way to locate a strayed animal), the Lost Coin (a woman goes out of her way to find a missing coin), and the Prodigal Son – one of the longest and most highly crafted of parables, where a father lavishly welcomes home a son who has squandered his inheritance on wild living in a faraway land. The son returns in a wretched state, barely alive. His father’s response is overwhelming: he kills a fatted calf to celebrate the homecoming of this “wasteful” or prodigal son. The son’s older brother, however, is not overjoyed by anything that unfolds before him. He has worked diligently beside his father for years. Now he finds the spectacle of his younger brother being feted in such a manner wholly extravagant and surely unearned. Fury and jealousy overwhelm him. But his father speaks to him with calm affection: “Son, you are always with me, and all that I have is yours. But it was fitting to celebrate, for this, your brother, was dead, but he’s alive again; he was lost, and now is found” (Luke 15:31-32).

Like others, such as Henri J. M. Nouwen (who wrote a memorable book on this parable), I’ve stood in awe before Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son in St. Petersburg, Russia, at the Hermitage. One of his last great paintings – he died in 1669 and completed this masterpiece in the two years before his death – it captures the moment of forgiveness and mercy essential to the parable. The bearded father’s expression is one of huge relief as he embraces a beloved son who was thought lost but has returned on his knees. His eyes glimmer with love as well as thanksgiving. The resentful older son peeks around a corner, in a darkness that is spiritual as well as physical. His resentment glowers. And yet one feels sorry for him, too. There is a kind of openness to pain in his expression. The light-drenched figures – father and prodigal son – blaze in the foreground. But one grieves for the elder son, who might well be the most important figure in this parable. He, too, is lost and needs forgiveness as well as compassion. The painting reaches forward in time, extending through it, dissolving it. The stillness of the image is indelible, an act of loving attention to a single frame of the parable, the action frozen but kinetic, reflective as well as expectant.

MIRACLES AND MINISTRY

The personality of Jesus, and his radical incendiary ministry, caught the attention of all who heard about it; his reputation spread rapidly through Galilee, where he dispensed his signs and wonders and spread the “good news” of a coming kingdom with astounding energy. In one of the memorable images of the public ministry, we find him standing in a boat in the Sea of Galilee and preaching to those on shore. Not a fisherman himself, he seemed to enjoy being in boats and often employed metaphors derived from fishing. We even find him walking on water in a moment emblazoned in the memory of most Christians throughout the centuries.

In that scene, Jesus walked toward his disciples during a storm, and yet they didn’t recognize him. “It’s a ghost;’ one of them cried (Matthew 14:26). Jesus responded with his typical reassurance and calm: “Be of good cheer; it’s me, so don’t be afraid.” Peter questioned him now, uncertain about the identity of this mysterious figure. But Jesus told him to come toward him. Peter took the risk, walking toward him over the water in a strong wind. When he grew frightened, his faith Withering, he sank into the waves. Jesus reached out to him, lifting him up. “O you people of little faith, why did you doubt me?” As soon as Peter resumed his trust in God, he was buoyed up.

The miracle of the loaves and fishes takes center stage in the gospels, for good reason. It’s the one where Jesus managed to feed five thousand men and women with just five loaves and two fishes, and there was still leftover food. (In a similar miracle, reported only in Mark and Matthew, Jesus fed four thousand.) It’s a miracle of abundance that occurs in the wake of the beheading of John the Baptist, terrible news that would certainly have upset Jesus and spread fear among his disciples. He withdrew to a small boat, grieving the loss of his cousin, who had inspired and baptized him. After a time of intense prayer, God directed him back into the world, where a crowd gathered around him in the countryside. He went straight to work, healing the sick, offering words of encouragement, and preaching the good news of God’s love. It grew late, however, and the disciples began to worry about the fact that nobody had eaten. They suggested that Jesus send the crowd into nearby towns for food. Jesus, however, insisted they should stay. Having been handed five loaves of bread and two fishes, he told the huge crowd to sit on the grass. Then he looked up to heaven and, like a magician-priest, broke the loaves and fishes into countless pieces, feeding everyone. Twelve full baskets of food were left over.

The point is that God will meet the needs of his people, even exceed them. It’s a message of abundance: there is always enough, even more than enough. Once again, an act of Jesus recalls a famous scene from Hebrew scripture; in Exodus, God (in the presence of Moses) fed the hungry Israelites with manna from heaven, a snow of bread in ridiculous profusion. The Moses link would have been a strong association in the minds of those fed by Jesus as well as those who later listened to this story as it arose in all four gospels, which suggests that it had a key place in the worship of early Christian communities. Whatever they required, God would provide.

Miracles of healing spin through the gospels, a key part of the work of Jesus, and one cannot ignore them.(32) But Jesus emphasized that he himself didn’t perform these miracles of healing but that the faith of the person being healed mattered a great deal. Jesus was merely an instrument of God, as in the healing of ten lepers in Luke, where he doesn’t say, “I did this for you.” He says, instead: “Arise, go your way: your faith has made you whole” (Luke 17:19). This is not, I think, contradicted by the passage in John where Jesus told skeptics to believe the works that he accomplished, even if they didn’t actually believe he was the Son of God: “Although you don’t believe in me, believe the works I do, so that you may know, and really understand, that the Father is in me, just as I’m in him” (John 10:38). Jesus felt the power of God within himself, and he could engender faith in those around him, and this faith had the power to heal.

THE END OF THE JOURNEY

As noted, we can’t know exactly how long Jesus and his disciples lingered in Galilee and its environs. But the time came when Jesus himself began to feel the pressure of his destiny, when he saw with absolute clarity that the contours of his life had begun to assume a mythic shape. This understanding may have come to him suddenly or gradually (I prefer the latter), as he walked and preached, healed and comforted. However it came about, he saw that he himself must become a kind of sacrificial, or paschal, lamb. This would be, indeed, the concluding phase of his mission. Jerusalem – the Holy City – now swung into view: he must go there with his disciples, on foot, passing through Judea and Perea. He had something in mind, perhaps inchoate at first but resolving and urgent: an image of himself as Messiah, the anointed one – or Christ. The spirit had been working in him for some time now, enlarging his consciousness, forcing revelations that he would share with those closest to him. He had developed a primal intimacy with God, and the spirit had begun to work, in him and through him, in ways that would affect everyone who came after. “Christ is born:” wrote Emerson, “and millions of minds so grow and cleave to his genius.”(33) But Emerson understood that the word “genius” only means “spirit” in Greek, and that it flows from Jesus into each us, as when we find in ourselves the divine spark. “Whenever the mind is simple,” Emerson continued, “and receives a divine wisdom, old things pass away.” And so a new world rises with the sun/son, breaking over the horizon, beckoning as we walk in the footsteps of Jesus, stopping by the wayside to listen to his simple, comforting, at times alarming words.

QUESTIONS FOR OUR DISCUSSION (October 17):

Jay Parini writes, “Jesus’ ministry became a series of encounters, one-on-one confrontations that changed the lives of those who met him, whether they came to him for healing or instruction. Some brushed against him by accident; yet few didn’t feel the force of their meeting with the Son of Man. Each felt the presence and power of his presence, his intense contact with the kingdom of God, his emotional and intellectual resources, the life-enhancing waters that flowed from him.” (see p. 45)

How do you think Jesus maintained his “intense contact

with the kingdom of God”?

When have you experienced contact with God’s “kingdom”?

What words would you use to describe your experience?

QUESTIONS FOR OUR DISCUSSION (October 24):

In his Beatitudes, Jesus used the word blessed in a way

that seems completely foreign to our way of thinking.

What did blessed mean to Jesus?

Jay Parini says that the Beatitudes can tell us what kind of man Jesus was.

Read through the Beatitudes again:

What do the Beatitudes tell you about Jesus’ personality?

Each morning of this next week, read one of the Beatitudes, and then reflect on its meaning throughout the day. Each evening, look back over your day for an example of that Beatitude in something that happened — or in someone you met.

1. The poor in spirit

2. Those who mourn

3. The meek

4. Those who hunger and thirst for righteousness

5. The merciful

6. The pure in heart

7. The peacemakers

NOTES – CHAPTER 4

1. See John 4:1-42, for the story in full. I compress and paraphrase.

2. I’m grateful to Cynthia Bourgeault for her reading of this episode in the life of Jesus in The Wisdom Jesus. My account draws on her throughout my discussion of this episode.

3. See Mark 3:2.2; Matthew 12.:2.2.-2.9; Luke 11:14-23.

4. See Wendy Cotter, “Miracle Stories, the God Asclepius, the Pythagorean Philosophers, and the Roman Rulers” in The Historical Jesus in Context, eds. A.J. Levine, D. C. Allison, and J. D. Crossan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 166-78.

5. Wilde, of course, was referring to the English here; more broadly, I suspect, he referred to the English tendency to think in the reductively super-rational ways of empiricism and analytic philosophy.

6. See Vermes, 181. He notes that Rabbi Akiba, and many respected Jewish teachers, made all sorts of allowances for breaking the Sabbath when it was deemed humane or sensible. But the hostility in the gospels toward the Pharisees speaks to their date of compositions, decades after the death of Jesus, when Jews had taken firmly against the idea of Jesus as the Messiah. The Pharisees had replaced the Sadducees as the Temple elite by now, and they were therefore the establishment, so they needed bashing.

7. See Krister Stendahl, The School of St. Matthew, and Its Use of the Old Testament, 2nd ed, (Philadelphia, Fortress, 1968).

8. Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), Jesus of Nazareth (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2.007),74.

9. Recounted by C. G.Jung in Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1963).

10. Liberation Theology arose from this first Beatitude, stressing the literal sense of the term “poor.” Gustavo Gutierrez, a Peruvian priest and theologian, published A Theology of Liberation in 1971, and he argued that Christ called his followers to pay close attention to those at the bottom of society. His writings have found a huge following in Latin America and Central America in particular. “The poor,” he wrote, “are a byproduct of the system in which we live and for which we are responsible.”

11. See Thich Nhat Hanh, Living Buddha, Living Christ (New York: Riverhead, 1995), 154. A Buddhist monk and renowned teacher, Nhat Hanh writes: “I do not think there is much difference between Christians and Buddhists. Most of the boundaries we have created between our two traditions are artificial. Truth has no boundaries.”

12. Aristotle, Nicomachian Ethics 4.5.3. See Bailey, 73.

13. Rudolf Bultrnann, Theology of the New Testament (New York: Scribner, 1955), 272.

14. Even if written before the fall of the Second Temple, these would have been stressful times for Jews within the boundaries of the Roman Empire. Most scholars place the date of composition after the Temple was destroyed.

15. Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America: Culture & Agriculture (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1977), 122.

16. Berry, 120.

17. John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Law and Love, Vol. IV (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 205-6.

18. I use a familiar version from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.

19. Most Protestants use the doxology. Catholics (using the Latin Rite) do not. The doxology echoes a prayer found in I Chronicles 29:11: “Yours, O Lord, is the greatness and the power and glory.” In the Greek and Byzantine liturgy, the priest usually sings the doxology.

20. For a thorough reading of The Lord’s Prayer in the context of the Exodus story, see N. T. Wright, “The Lord’s Prayer as a Paradigm for Christian Prayer;’ in Into God’s Presence: Prayer in the New Testament, ed. Richard N. Longenecker (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 132-54.

21. The word translated as “daily” in Greek (epiousious) is extremely rare, and it probably means “ongoing” or “continuing to be required” – translators have taken a stab at a decent English equivalent, and “daily” from the KJV seems as good as any. It has certainly lodged in the collective memory.

22. See Elaine Pagels, Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation. (New York: Viking, 2012). It’s not surprising that many early church leaders thought this book should not be included in the canonical New Testament. Even Martin Luther, early in his career, thought this apocalyptic vision had nothing to do with Christianity.

23. The Rosary is largely focused on a prayer to Mary that incorporates two verses from Luke: “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and in the hour of our death.”

24. For a complete survey of this idea in world religions, see Jeffrey Wattles, The Golden Rule (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). Wattles regards the “rule” as not the embodiment of a single idea but a concept that embraces growth on many levels.

25. This is David Hinton’s translation.

26. This Babylonian code – the foundation of all Western law – was discovered in 1901.

27. It’s interesting to note how many significant texts within Judaism emerged within a context of crisis and exile, such as the Lurianic Kabbalah in the late sixteenth century. Isaac Luria (1534-1572) was a mystic whose arcane writings attracted a huge following among exiled Jews – the Sephardim – who had been driven from Spain by Ferdinand and Isabella.

28. John Drury, The Parables in the Gospels (New York: Crossroad, 1985), 21

29. Comical efforts to interpret this saying in ways that make it less difficult for the rich to swallow have appeared over the centuries, including the bogus idea that there was a gate in Jerusalem called “the camel,” and that merchants had to unload their belongings to get through it. No such gate existed, alas. It may well be that the gospel saying turns

on a misprint: kamilos (camel) in Greek could easily have been written as kemelos, meaning cable or tope. In other words, it’s easier to thread a needle with a rope than for a rich man to enter heaven. It’s more probable, of course, that Jesus simply means that it’s not easy for a rich man to enter heaven, given that “Blessed are the poor.”

30. Drury, 60.

31. See C. H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom (New York: Scribner, 1961) and Joachim Jeremias, The Parables of Jesus, trans. S. H. Hooke, 2nd ed. (New York: Scribner, 1954). Much of this work builds on the scholarship of Adolf Julicher (1857-1938), who emphasized the central importance of the “kingdom of God” in the parables.

32. The basic Christian argument for belief in the miracles of Jesus will be found in C. S. Lewis, Miracles (London: Collins, 1947).

33. Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance.”