© Jay Parini. Reproduced by permission of the author.

QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR READING:

What is metanoia?

Over the years, when have you experienced metanoia?

What could new metanoia mean for you today?

What could metanoia mean for your home?

For your town? For our country?

PREFACE

Take my yoke upon you and learn from me,

for I am gentle and humble in heart,

and you will find rest for your soul.

For my yoke is easy and my burden light.

– Matthew 11:29-30

The soul of man is the lamp of God.

– Hebrew Proverb

This is a biography of Jesus, not a theological tract, though I take seriously the message embodied in the story of Christ that unfolded in real time. In Jesus: The Human Face of God, I offer a fresh look at him from the viewpoint of someone (a poet, novelist, and teacher of literature) who regards scripture as continuous revelation, embodied not only in the four gospels – still the main source for information about the life of Jesus – but also in extra-canonical writing, such as the Gnostic Gospels, as well as in centuries of poetry and literature, where we see that prophecy remains active and ongoing. I emphasize throughout what I call the gradually realizing kingdom of God – a process of transformation, like that of an undeveloped photograph dipped in chemicals. The process itself adds detail and depth to the image, which grows more distinct and plausible by the moment.

Literal-minded readings of the scriptures distort this understanding of the kingdom of God in unfortunate ways. In my view, one is not “saved” by simply checking off the boxes in a code of dogmatic beliefs – this is not what Jesus had in mind. He asked more of us than that, and offered more as well. And so, in this portrait of Jesus’s life and ideas, I put forward a mythos – a Greek word meaning story or legend – which suggests that the narrative has symbolic contours as well as literal heft, and that one should always read this story with a kind of double vision, keeping in mind the larger meanings contained in the words and deeds that have mattered so much to Christians over two millennia.

Modern theologians have talked about demythologizing Jesus, but I want to remythologize him. At every turn in this biography, I try to imagine what Jesus meant to those who encountered him, and how his teachings and behavior inspired deeply personal transformations with public or social (even political) implications.

Jesus was a religious genius, and the Spirit moved in him in unique ways, with unusual grace and force, allowing him access to the highest levels of God-consciousness. His own life provided an example of how to behave in the world, urging us to love our neighbors as ourselves, to turn the other check when struck, and to remain fixed on “faith, hope, and love.” “This is my commandment,” Jesus said, putting before us a single ideal, “That you love one another, as I have loved you” (John 15:12). The simplicity and force of this statement take away the breath.

In the course of this book, I make an effort to place Jesus and his teachings within the context of desert wisdom. He came into this world at a turning point in history, a devout Jew trained in the laws of Moses and the traditions of Judaism. But he lived on the Silk Road, where he had access to Eastern as well as Western ideas. These currents informed his thoughts, and the Sermon on the Mount – where the core of his teaching lies in compressed form – extended and transformed key Jewish concepts while absorbing the Hindu and Buddhist idea of Karma: the notion that we ultimately reap what we sow. Jesus thought of the human mind in Greek terms, of course: an amalgam of body and soul. Yet his understanding of the human condition drew on every available concept as he set forth at the age of thirty with energy and passion, hoping to reshape the world, speaking not to elites – those who ruled the Roman Empire or administered the Second Temple in Jerusalem – but to the poor, the weak, and the marginalized. Here was, indeed, a revolution.

He was a ferocious, challenging teacher, hardly the Jesus “meek and mild” of the church hymn. And he made huge demands on those drawn toward him, as when he says in Mark 8:34: “Whoever will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me.” It’s an audacious invitation and one that Christians rarely take with the seriousness intended. The Way of Jesus, as it might be called, involves self denial, a sense of losing oneself in order to find oneself, moving through the inevitable pain of life with good cheer, accepting gracefully the burdens that fall on our shoulders and the tasks that lie before us. This is true discipleship,

On this subject, I often recall the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian and minister who was executed by the Nazis in a concentration camp at Flossenburg on April 9, 1945, only a few weeks before its liberation by the Allies. Bonhoeffer stood up boldly to Hitler, and his anti-Nazi activities led to his arrest by the Gestapo. During his imprisonment in Berlin’s Tegel Military Prison for a year and a half, Bonhoeffer offered comfort and inspiration to his fellow prisoners, and even his Nazi jailers admired his courage and compassion, the example he set for others in a dire situation. He imitated Jesus there, making use of his example, allowing it to define his own life and actions.

Bonhoeffer reflected passionately on the meaning of his life, writing in his diary only a few months before his death: “It all depends on whether or not the fragment of our life reveals the plan and material of the whole. There are fragments which are only good to be thrown away, and others which are important for centuries to come because their fulfillment can only be a divine work. They are fragments of necessity. If our life, however remotely, reflects such a fragment … we shall not have to bewail our fragmentary life, but, on the contrary, rejoice in it.” (1)

In The Cost of Discipleship, a bracing theological work, Bonhoeffer meditates at book-length on what it means to take up the cross: “Discipleship means adherence to Christ, and, because Christ is the object of that adherence, it must take the form of discipleship. An abstract Christology, a doctrinal system, a general religious knowledge on the subject of grace or on the forgiveness of sins, render discipleship superfluous, and in fact they positively exclude any idea of discipleship whatever, and are essentially inimical to the whole conception of following Christ.” (2) So it won’t do simply to follow a doctrinal system, marking off the things one has to believe in order to be “saved.” To follow the Way of Jesus, one has to walk in a certain direction, experiencing the difficulties as well as the illimitable freedom of that choice. “Happy are the simple followers of Jesus Christ who have been overcome by his grace,” writes Bonhoeffer. “Happy are they who, knowing that grace, can live in the world without being of it, who, by following Jesus Christ, are so assured of their heavenly citizenship that they are truly free to live their lives in this world.” (3) Bonhoeffer’s statement makes one question the idea of dogma, the notion that one should adhere to strict rules and prescribed statements in order to pursue the Christian way.

Jesus himself would have been startled to learn that, only a few centuries after his death – with the conversion of Emperor Constantine in the early fourth century – the Roman Empire itself would officially adopt his teachings and make them the law of the land. He might well have balked at the thought that a world religion would arise in his name, with competing theologians (and armies), all convinced that their understanding of his gospel message is correct, while other views are wrong. Jesus had no intention of founding a church (Greek: ekklesia) in competition with Judaism, although as the parable of the mustard seed suggests, he could imagine large numbers of people flocking to his tree of ideas like birds.

In the last chapter of this book, I explore the “afterlife” of Jesus, how a church gradually formed, with competing ideas about what his life meant. I also explore the various attempts to write about his life, which in the modern age began in the eighteenth century, when after the Enlightenment a degree of skepticism arose about the historical status of Jesus and the deeds and words relayed in the gospels. But that’s later in the story. The starting point, for me – as suggested above – is the world into which Jesus was born, a pervasively Jewish world in Palestine at one of the major junctures in history, when the message that Jesus offered struck a small chord among a core group of people – most of them Mediterranean peasants who could barely read or write – that would grow louder and more resonant in time.

Yet questions loom: Who exactly was this man, Jesus of Nazareth? Was he, as some scholars argue, a wandering rabbi, a magician, a healer and exorcist like many others at this time, including Rabbinic sages such as Honi ha-Ma’agel or Hanina ben Dosa?(4) Was he also an apocalyptic visionary who imagined an end to history? As anyone who reads the gospels soon notices, Jesus quoted easily and often from Hebrew scriptures, with incredible alertness to parallels that foreshadowed his own story. He understood that Jews in Palestine felt profoundly uneasy under Roman rule, and he reflected this political reality in the things he said and did. But it’s important to keep in mind that he was always a good, if unconventional, Jew. The fact that he took himself to be the long-awaited Christ (the Greek word for messiah) would, in fact, hardly have endeared him to Jewish authorities, who never imagined that the Chosen One would come from peasant stock in a remote Galilean village. That wasn’t what they had in mind, and they looked askance at his purveyance of “signs and wonders” – miracles and astounding deeds that drew crowds wherever he went.

Christians have sometimes turned away from the supernatural aspects of his life with a sense of embarrassment. Walking on water? Giving sight to blind men? Healing lepers? Turning water into wine? Bringing the dead back to life? Rising from the dead after being crucified? Thomas Jefferson and Leo Tolstoy – both sons of the Enlightenment – sifted through the gospels with great care and a red pencil, underlining the aphorisms where his wisdom shone; at the same time, they crossed out the supernatural parts, including the Resurrection, which they assumed no self-respecting intellectual could abide. In What Is Religion? Tolstoy puts his views forward without fudging his skepticism: “Religion is not a belief, settled once for all, in certain supernatural occurrences supposed to have taken place once upon a time, nor in the necessity for certain prayers and ceremonies; nor is it, as the scientists suppose, a survival of the superstitions of ancient ignorance, which in our time has no meaning or application to life; but religion is a certain relation of man to eternal life and to God, a relation accordant with reason and contemporary knowledge.” (5)

To this day liberal Christians tend to deflect the “superstitious” parts of the Jesus story and prefer to see religion as “a relation accordant with reason and contemporary knowledge,” with Jesus as a prophet who preached love and nonviolent resistance to evil. He becomes simply a wise man who wished us to behave like the Good Samaritan in the parable (Luke 10:29-37), that kindly fellow who went out of his way to help a robbed and beaten traveler who lay by the roadside. This was ethical behavior of a high order, and Jesus encouraged such habits of rectitude and responsibility. Love your neighbor. Treat people as you would treat yourself (unless you happen to treat yourself badly).

This Jesus stands in contrast to the Jesus of evangelical Protestantism, where he becomes the Savior, the single doorway to heaven, the only route to eternal life, the way to ward off the flames of hell. Indeed, we’re all familiar with the bumper sticker versions of this theology, perhaps best summed up as “Jesus Saves.” For such Christians, the Redeemer was required by his father in heaven to die for the sins of humanity. In this tradition, simply believing that he gave his life for our sins buys admittance to God’s kingdom. This is widely known as conversion: “Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, and you will be saved, and your house,” as we read in Acts 16:31. It’s a simple idea, attractive to large numbers of people, although such a picture of Jesus and his “good news” tends to oversimplify his message and meaning, leading to a kind of limited vision that is both reductive and – in my opinion – dangerous. It suggests that one can, in an instant, cross a magical line and acquire salvation instead of entering into the gradually realizing kingdom of God, a process of daily transformation.

JESUS INVITES US TO “STRETCH” OUR MINDS

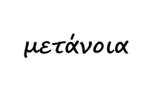

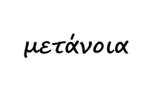

Jesus invited, even insisted on, a change of heart, asking us to repent. But repentance is only part of the deeper meaning buried in the Greek term μετάνοια (metanoia) – a key word in the New Testament. The word derives from meta, meaning “to move beyond,” as in metaphysics, or “grow large or increase.” Noia means “mental” or “mind.” So the word, quite specifically, means: “to grow large in mind.” When scriptures suggest that one should “repent” in order to be “saved,” this actually means that in addition to having a change of heart – and that remains a core meaning here – one should go beyond the mind, reaching for awareness of the spirit, for a deep grounding in God. Even to be “saved” doesn’t relate to “salvation” in the most common sense of the term: soteria in Greek. It means “being filled with a new spirit.” In other words, one shifts consciousness, through prayer and meditation, through worship, seeking a larger and wider consciousness. One wakes up into the kingdom, moving beyond the deadening confines of everyday reality.

This is very different from the usual focus on repentance and salvation, concepts that actually derive from the early Church Fathers, especially Justin Martyr, who influenced Irenaeus and Tertullian, early theologians who focused on the need for remorse, for expiation – getting rid of one’s sinful deeds by admitting them. St. Jerome, who translated the Bible into Latin in the late fourth century, absorbed this teaching, and he set in motion a range of theological misperceptions by translating metanoia as paenitentia, which becomes, in English, repent, as in the King James Version (KJV): “Repent ye, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand!” (Matthew 3:2) .

This translation does not reflect a properly complex version of the term metanoia (which occurs fifty-eight times in the New Testament). The word itself suggests a beckoning by God toward the human soul, an invitation to spaciousness and awakening. (6) It implies a reaching beyond (meta) the mind (noia), a wish to acquire a wider spiritual awareness. A better way to translate this verse in Matthew would be: “Have a true change of heart and wake up to God. The spaciousness of his kingdom lies inside you. Transformation is not only possible: it lies within your grasp.” This, for me, is what it means to be “saved,” and it asks more of us than mere assent to a list of beliefs. It requires a mindfulness and absorption of God’s kingdom that is, in the end, life changing.

While not a biblical scholar, I have over many years been in close contact with Christianity and Christians from different (often conflicting) theological traditions. Growing up in the home of a former Roman Catholic turned Baptist minister, I often sat through hot summer evenings in tabernacle meetings of a kind familiar to anyone who has watched Billy Graham on television. Indeed, I heard the Reverend Graham in person on more than one occasion, and countless times on television and radio – my family listened every Sunday at lunchtime to his weekly radio sermon. I continue to have genuine sympathy for what might be called “that old-time religion.” Every morning at the breakfast table, my father read from the King James Version of the Bible, large portions of which I committed to memory. I later studied the Greek New Testament, reading a good deal of theology in college, graduate school, and beyond. Christian theology has been a preoccupation of mine for some five decades. (I should note that most of the versions of the New Testament quoted in this book are my own, produced by working from an interlinear Greek-English text. For reasons of familiarity I sometimes prefer the King James Version, as when I quote the Beatitudes or the Lord’s Prayer. I use the KJV in all cases when quoting from the Hebrew scriptures. To my ear, it’s what the Old Testament sounds like.) As a young man I became, and I remain, a member of the Episcopal Church, with an Anglican disposition – a consequence of ten years spent in Britain, perhaps.

My religious affections range widely, probably as a result of the mongrel past described above. At the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland, I wrote a graduate thesis on Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit movement and an innovator in the field of devotional practice, as seen in his Spiritual Exercises, which dates to the early sixteenth century. In college, I was thoroughly enamored of modern theologians like Paul Tillich and Rudolf Bultmann, who brought my evangelical orientation into question; yet I retain a sympathy for the religion of my childhood: my heart warms when I hear hymns like “Blessed Assurance” or “Just as I Am.” My own religious practice, however, draws on many strands in Christianity, and my reading in the field ranges over any number of (often contradictory) spiritual writers, many of them as much influenced by Buddhism as Christian theology. (I regularly teach a course on poetry and spirituality at Middlebury College, bringing me into constant contact with a range of spiritual writing from the Psalms through the Tao Te Ching, the poems of Rumi, as well as T. S. Eliot, R. S. Thomas, Charles Wright, and Mary Oliver, among others. In fact, I write as someone who has spent more time reading poetry than scholarly studies of Jesus.) Although I will allude frequently to competing interpretations of biblical texts, my focus will remain on my own understanding of the meaning of the life of Christ – provisional as this must necessarily be.

In the final chapter of this book, I attempt to deal with the often contradictory efforts of scholars in recent centuries to locate the historical foundations of the Jesus story: the so-called quest for the historical Jesus. It’s not easy work, as the biblical trail alone is often blurry, and the usual techniques of “scientific” history rarely apply here. The gospels themselves can’t be considered historical evidence in the modern sense of that term. But in my attempt to reimagine the mythos of Jesus, I try to take all this uncertainty into account, retelling the story as I see it, noting the difficulties of interpretation where they arise, drawing attention to contradictions where they exist, while trying to see Jesus steadily and whole through the kaleidoscopic lens of many texts.

Now in my mid-sixties, I’m still in search of Jesus, and this seeking often seems more important than the finding. To a large degree, this biography itself represents the fruit of my decades-long project of trying to understand Jesus and to take his example purposefully in my own life. I often recall some lines from the Gospel of Thomas, one of the Gnostic Gospels discovered in the sands of Egypt at Nag Hamrnadi in 1945:

If you are searching,

You must not stop until you find.

When you find, however,

You will become troubled.

Your confusion will give way to wonder.

In wonder you will reign over all things.

Your sovereignty will be your rest. (7)

This search, for me, involves a great deal of confusion, although it often gives way to wonder, to a feeling of all-embracing peace and sympathy for others. Jesus invites me to consider the lilies, and to understand that, by grace, I have access to a wider kingdom than I’d previously imagined. It’s a matter of “thy will be done,” not my own willing: a shift of emphasis that lifts the burden.

While I pay close attention to the facts in this biography of Jesus, the historicity of his life is less important than the meaning of the story itself. It doesn’t matter what aspects of his life – his sayings, the exemplary deeds that formed the core of his ministry, the miracles – can be confirmed (or denied) by historians. At the end of his recent book, Constructing Jesus, Dale C. Allison, Jr. – a leading New Testament scholar – concludes his long study with a moving frankness: “While I am proudly a historian, I must confess that history is not what matters most. If my deathbed finds me alert and not overly racked with pain, I will then be preoccupied with how I have witnessed and embodied faith, hope, and charity. I will not be fretting over the historicity of this or that part of the Bible.(8) This rings true in my ears.

What matters is the way that God moved in the life of Jesus, who showed us how to find this spirit within ourselves. Ralph Waldo Emerson put the matter succinctly in his “Divinity School Address” delivered at Harvard in 1838:

Jesus Christ belonged to the true race of the prophets. He saw with open eye the mystery of the soul. Drawn by its severe harmony, ravished with its beauty, he lived in it, and had his being there. Alone in all history he estimated the greatness of man. One man was true to what is in you and me. He saw that God incarnates himself in man, and evermore goes forth anew to take possession of his world. He said, in this jubilee of sublime emotion, “I am divine. Through me, God acts; through me, speaks. Would you see God, see me.”

The story of Jesus transcends time and physical boundaries. To understand it, one must remain open to every possibility, regarding the miracles of Jesus and the Resurrection as mysteries more alluring than frustrating, more inspiring than disconcerting. I narrate the life of Jesus from Bethlehem to Golgotha and beyond – with sympathy for its profound mythic pull, its transforming powers. I stop by the wayside to explain major moments or concepts that may not be familiar to all readers, such as the Virgin Birth or the Transfiguration. In the process of remythologizing Jesus, I take in stride the supernatural aspects of his life, believing that reality is more complex than we usually think, and that we can’t begin to imagine the truth of things with the limited intellectual and perceptual machinery we’ve been given. In this, I follow St. Anselm, who referred to “faith on a quest to know:’ writing: “For I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand. (9)

Within the Christian worldview, history becomes a pattern of timeless moments. And the work involves trying to find a place in the bewildering universe of hints and guesses that confront us as we search, looking around us at things we can scarcely hope to comprehend with the limited intellect and resources we’ve been given. As T. S. Eliot put it so beautifully in “The Dry Salvages”:

These are only hints and guesses,

Hints followed by guesses; and the rest

Is prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action.

QUESTIONS FOR OUR DISCUSSION:

How would you explain the Greek word metanoia?

Over the years, when have you experienced metanoia?

What could new metanoia mean for you today?

What could metanoia mean for your home?

For your town? For our country?

NOTES — PREFACE

1 Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1959), 33.

2 Bonhoeffer, 59.

3 Bonhoeffer, 55-56.

4 For a discussion of the Jewish context of Jesus, see Geza Vermes, Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels (London: Collins, 1973) or Daniel Boyarin, The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ (New York: The New Press, 2012).

5 Last Steps: The Late Writings of Leo Tolstoy, ed. Jay Parini (London: Penguin, 2009), 164.

6 For a fuller discussion of metanoia, see Cynthia Bourgeault, The Wisdom Jesus: Transforming Heart and Mind – a New Perspective on Christ and His .Message (Boston: Shambhala, 2008), 37-38. See also Murray A. Rae, Kierkegaard’s Vision if the Incarnation: By Faith Transformed (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). My reading of metanoia is also reinforced by Marcus J. Borg, Jesus: Uncovering the Life, Teachings, and Relevance of a Religious Revolutionary (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2006), 219-20. Borg says: “The Greek roots of ‘repent’ mean ‘to go beyond the mind that you have.’”

7 The Gospel of Thomas: Wisdom of the Twin, ed. Lynn Bauman (Ashland, OR: White Cloud Press, 2004), 8. I am grateful to Cynthia Bourgeault for directing me to this translation.

8 Dale C. Allison, Jr., Constructing Jesus: Memory, Imagination, and History (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2010), 462.

9 Anselm of Canterbury, Proslogion, The Major Works, trans. M.J. Charlesworth (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 87.

Acknowledgments

It would be impossible to acknowledge all of those who have helped me along my path over many decades in my pursuit of Jesus, but several friends read this manuscript in various drafts, including a number of gifted theologians and biblical scholars. These include Ellie Gebarowski Bagley, J. Stannard Baker, Edward Howells, Paul Jersild, John Kiess, Richard McLaughlan and O. Larry Yarbrough. Without their encouragement and suggestions, this book would have been infinitely poorer, although I accept full responsibility for all errors of fact and judgment. The manuscript was closely read by my editor and friend, James Atlas, and by my wife, Devon Jersild. Their suggestions were acutely intelligent and always helpful as well as encouraging.