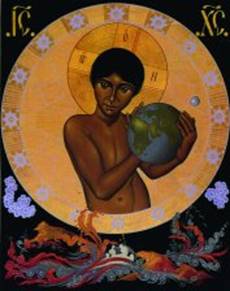

Christ and the ecological economic worldview

Jesus embraces the world (icon, late 20th century)

The most certain thing we know about Jesus, according to current scholarship, is that he was a teller of stories and a speaker whose purpose was the transformation of perception. Jesus was opposed to the various forms of domination of his time Above all else, he invited people to imagine a different life, one centered in God and inclusive of all others – and then to live that life.

How is this portrait of the historical Jesus relevant to an ecological Christology? John Dominic Crossan names the Parable of the Feast as central to what Jesus means by ‘the Kingdom of God.’ In this parable everyone is invited to the table; Crossan writes, “If beggars come to your door, you might give them food or even invite them into the kitchen for a meal, but you don’t ask them to join the family in the dining room or invite them back on Saturday night for supper with your friends. But that is exactly what happens in this story.” (see p. 173)

For first-century Jews, the key boundary was purity law: one did not eat with the poor, women, diseased, or the ‘unrighteous.’ For us today, the critical barrier is economic law: one is not called to the just or sustainable allocation of resources with the poor, the disadvantaged, the ‘lazy.’ And yet, in both cases, the issue is the most basic bodily one – who is invited to share the food?

Correct ‘table manners’ are a sign of a just society, a sign of the Kingdom of God. At the center of Jesus’ message as prophet and teacher is a vision of the world as an egalitarian community of beings, not a hierarchy of individuals. Jesus’ unsettling parables and sayings are embodied in his own practices of living among the marginalized and siding with those considered inferior by conventional standards.

Again, Crossan writes, “The Kingdom of God … began at the level of the body and appeared as a shared community of healing and eating – that is to say, of spiritual and physical resources available to each and all without distinctions, discriminations, or hierarchies. One entered the Kingdom as a way of life, and anyone who could live it could bring it to others. It was not just words alone, or deeds alone, but both together as life-style…. The Kingdom of God is what the world would be if God were directly and immediately in charge.” (see p. 174, 177)

There appears to be a solid link between Jesus’ vision of society and what we are describing as the ecological economic worldview. Sin, for today’s Christians, is refusing to acknowledge that link – or explaining it away because we will not accept the consequences of our privileged lifestyle. We are not invited to believe in something, but to live differently – and that is not principally a matter of the intellect or the will, but of the heart.

There have been some people who approach this ideal – we call them saints, and they appear in all religious traditions. The saints combine God-intoxication and universal compassion for others; through them we see the Spirit of Jesus, who invited people into a new way of seeing for a new way of living.

This, quite simply, is the way of ‘deification,’ a reflection of God’s life and the attempt to become like God. This picture of Jesus, emerging from recent scholarship and the lives of myriad followers over 2,000 years give us a sense of the way to the new life: it is only possible by relying utterly on God and, by so doing, developing the capacity for selfless love for others.

Annie Dillard, in For the Time Being, lays out a grim picture of human existence – from “bird-headed dwarfs, AIDS, and childhood leukemia to tornadoes, earthquakes, and floods. Life is a mess and a misery… Now and then, however, to those who seek God, God grants that they see ‘an edge’ of the divine. This gift is so overwhelming that “Having seen, people of varying cultures turn to aiding and serving the afflicted and the poor.” ( see p. 178)

So what does it mean for ecological Christology to say that reality is good?

We can say “Reality is good” because we believe God is with us (Jesus points to the source of love and power in the universe): we believe God is with us (on our side, working with us to bring fulfillment to all); and we believe that God is with us (all of us, all life, and especially the needy).

We can say “Reality is good” because we believe that life conquers death. We believe Jesus’ resurrection is a promise from Reality itself – God – that death is not the last word.