Richard Rohr writes,

Richard Rohr writes,

THE RESENTED BANQUET

Understanding God’s grace is the key that unlocks the Bible’s deepest message.

God eternally gives himself away – for no good reason except for love:

Happy are those servants whom the master finds awake.

I tell you he will put on an apron, sit them down at table, and wait on them.

(Luke 12:37-38)

In this parable Jesus paints a picture of God waiting on us – in the middle of the night! That’s not our usual image of God at all. We like to be found worthy, and we certainly want to understand before we accept things. We also expect a world of scarcity, or at least a world of ‘quid pro quo’.

Grace: the key that opens the Bible’s deepest theme

In the Hebrew Scriptures, the theme of God’s overflowing grace begins with manna and quails in the desert, and water gushing from a rock (Exodus 16-17); grace continues when Abraham and Sarah welcome angels in the desert (Genesis 18); grace eventually develops into an entire ritual for eating sacred foods (Leviticus 8:31f).

In the Gospels, we find Jesus at the welcoming table – perhaps a meal with sinners, or Pharisees, or a wedding banquet. At his Last Supper, he tells his disciples that this banquet is a foretaste and promise of what they will do forever in God’s kingdom (Mark 14:25, Luke 22:16; Matthew 26:29). There are ‘bread and fish’ meals where people experience overflowing abundance: the loaves and fishes story told by all four gospels (Mark 6:30f,, Matthew 14:13f, Luke 9:10f, John 6:1f); the breakfast on the beach with the Risen Jesus after a miraculous catch of fish (John 21:1f). There are ‘bread and wine’ meals: the Last Supper (Luke 22:14f, Matthew 26:26f); and the Risen Jesus breaking bread with his disciples on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13f).

But it takes a long time for us to be willing to come to the banquet. In real life as in Jesus’ parables, people have tended to resent the banquet, fear it, deny it or make it impossible (for themselves and others) to attend. We are either afraid or unwilling to just receive the gift of divine union.

We expect rewards and punishments; and only grace can move us beyond a list of ‘requirements’ to a religion that transforms our consciousness. As long as we remain inside of a win-lose script, we will always honor duty instead of expecting delight, and look for ‘jars of purification’ at the wedding (John 2:6) instead of the 150 gallons at the end of the party! (How did we avoid the clear message on that one?) We have kept the basic story-line of all human history in place and simply laid the gospel on top of it, like frosting on a cake.

For instance, we hear the parable of the laborers in the vineyard who worked only for an hour, but got paid the same as those who worked all day (Matthew 20:1f) – but seldom do we really get Jesus’ point – everyone will get the same reward, which is to sit with the Lord at the welcoming table.

For instance, forgiveness: By the the 4th century, the church was already trying to control the process of forgiveness through rules and penitential liturgies. But when forgiveness becomes largely a juridical process – when we can measure it out, or try to earn it, or find ways to exclude the unworthy – we destroy the likelihood that people will ever experience the pure gift of God’s forgiveness. Forgiveness is only and always pure gift – and that is precisely the experience that changes us so deeply.

God’s grace comes to David

In the Bible God’s grace starts with creation, and continues in God’s choice of ordinary people for extraordinary tasks.

King David’s remembered ‘holiness’ came from God’s presence in his life, not from his own actions. David was a violent warrior and an adulterer, but – by God’s grace – he eventually realized that whatever worthiness he had was a gift from God.

The prophet Nathan publicly exposed David’s sins (2 Samuel 12:13f), and here we see David in a deep struggle with his shadow self. This is the only time in the Bible where a king is confronted by a prophet and the king acknowledges that he is wrong and the prophet is right!

The problem isn’t sinning nearly as much as our unwillingness to admit that we have sinned. Jesus himself is never upset at sinners. He’s only upset with people who don’t think they’re sinners.

Toward the end of his life, David wanted to build Yahweh a house to prove how great he was. But Yahweh said to David, “I will build you a house.” (2 Samuel 7) We all start by thinking we are going to do something for God, and by the end of our lives we know that God has done it all for us.

Israel’s God of grace

“Yahweh, Yahweh, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness…” (Exodus 34:6-7)

The word that is translated ‘steadfast love’ has often been called ‘covenant love’; today we call it ‘unconditional love’.

The Bible presents the covenant as a bilateral agreement between the people and God (Exodus 24, Joshua 24, (Nehemiah 8:12f). But covenant love turned out to be a one-sided love, because there were very few times when Israel (or we) kept our side of the relationship.

After the great flood, God extends the covenant to every living creature on earth (Genesis 9:16). Centuries later, it would become a ‘new covenant’ written by God in human hearts, not religious laws (Jeremiah 31:31). The prophet Isaiah would repeat the same theme; after telling the people their religion is phony, God says “I will love you at even deeper levels, because I am determined to win. Your pettiness is not going to determine or limit my greatness” (Isaiah 29:13). In Ezekiel’s vision of the dry bones, God completely disqualifies Israel as a worthy people, but then promises to rebuild Israel from the bottom up (Ezekiel 36-37).

Grace and eternal life

The metaphor of hell – the tragic and eternal fire that awaits sinners – is an archetypal metaphor used by Jewish teachers down to Jesus himself. But later generations of Christians, without realizing what they were doing, used the metaphor of hell to turn the message of a loving God into a message about a God who tortures eternally.

But Jesus never said, “Be good now, and I will give you a reward later.” All of his healings were clearly for now. Christians literalized the metaphor (thinking that eternal suffering actually happens) and localized it (thinking that hell is a real place of fire under the earth).

You cannot prepare for love by practicing fear. Here is the real message: What we choose now, we will receive later. The spiritual life is quite simply ‘practicing for heaven’. If you want it later, do it now – how you get there determines where you will finally arrive.

The banquet as an image of grace

The banquet is Jesus’ most common image for what God offers us.

The banquet parables confuse us because we have assumed that Jesus’ teaching was primarily about moral behavior – and certainly ‘bad’ people should not be invited to a banquet! But when we realize that Jesus’ teaching isn’t about how to climb ladders of perfection – but how to allow God to carry us upward – then we can see his parables as God’s invitation to union.

Luke 14 has three banquet stories. In response to the banquet invitations, people make excuses, or try to create seating hierarchies when they arrive, or simply refuse to come. But Jesus responds, “When you have a party, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind – that they cannot pay you back will mean you are blessed” (Luke 14:13). You will be blessed, you will feel blessed, because now you will have a different worldview, and can see a world of abundance instead of a world of scarcity.

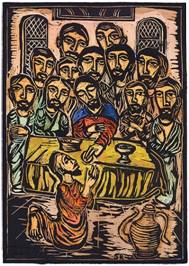

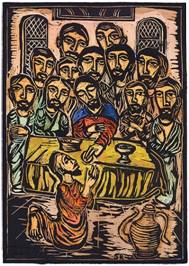

Jesus’ banquet theme culminates with the Last Supper itself. After the Resurrection, the disciples remembered his welcoming table, and were not afraid, at least in the early church, to follow his example (1 Corinthians 11:18-20). And so the Last Supper became the church’s ongoing banquet – its Great Thanksgiving, the Eucharist.

Yet even the Eucharist has been presented as a reward system for good behavior or correct belief. But the Last Supper included those who couldn’t possibly have understood what Jesus was teaching them, as well as two betrayers. That’s the way Jesus always transformed the contaminating element – through inclusion.

Feeding Judas – by Solomon Raj

Feeding Judas – by Solomon Raj

God’s grace comes to Mary

Mary understands that God does not need worthiness ahead of time; God creates worthiness by the choice itself.

God is the eternal ‘I’, always waiting for those – like Mary – who are willing to be a ‘Thou’. Mary’s ‘yes’ to God is an icon of prayer; the part of us that says ‘yes’ to God is the Holy Spirit praying within us.

By the end of the Bible we will see the New Jerusalem descending to earth, unearned and unprepared for (Revelation 21:2). After an entire Bible of warring, arguing, protecting, earning, competing, buying and selling of God, the gift is simply given and handed over to us. Yet the struggle – arguing, protecting ourselves, achieving merit, competing for rewards, even buying and selling God – is ultimately necessary. The struggle carves out the space within us for deep desire.

God both creates that desire and fulfills it. Our job is to desire God’s presence and our ‘yes’, like Mary’s, is still necessary.

Babette’s Feast

Rohr concludes this chapter of grace by retelling the classic story of ‘Babette’s Feast’: Babette decides to prepare a sumptuous banquet for the entire community. The people resist Babette’s invitation, but finally agree to attend. They decide to eat the food, but not to enjoy it.

At the end of the marvelous feast (which they have finally enjoyed), the worthy general stands up and speaks:

“Humanity, my friends, is frail and foolish. We have all of us been told that grace is to be found in the universe but in our human foolishness and shortsightedness we imagine that divine grace is finite and for this reason we tremble.

The moment comes when our eyes are opened, and we see and realize that grace is infinite. Grace…demands nothing from us but that we shall await it with confidence and acknowledge it in gratitude. Grace… makes no conditions and singles out none of us in particular; grace takes us all… to its bosom and proclaims general amnesty.

That which we have chosen is given to us, and that which we have refused is… granted to us. Ay, that which we have rejected has been poured upon us abundantly.” (Isak Dinesen, “Babette’s Feast).

Understanding God’s grace – God’s unstoppable love – is the key that unlocks the Bible’s deepest message: God eternally gives himself away – for no good reason except for love.

Questions for your reflection:

Think back to a time when you were an honored guest at a banquet. The food may have been sumptuous or simple, but it was prepared especially for the occasion, and you felt pure love.

What made this banquet one of special love for you?

What specifically do you remember about the meaning of the occasion?

What foods added delight and joy to the occasion, and why?