Liberating God of Life

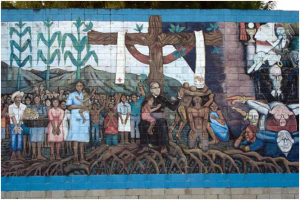

Oscar Romero Mural in San Salvador

Here the martyred Oscar Romero of El Salvador bears his bullet holes.

Romero had said, “If I am killed, I will be resurrected in my community.”

(1) The context – wretched poverty: In Latin America, decisions made by European conquerors in the 16th century – and continued by their descendants – led to widespread poverty and oppression. For centuries, Catholic Church leaders were complicit in this situation; but by the second half of the 20th century, Latin American theologians were developing Liberation Theology.

(2) Intuition of God’s presence and action: Traditional Christian doctrine presented God as the supreme being who made all things, governs the world as an all-powerful king, but still allows grievous poverty and suffering; peace and justice will come in eternal life. This theology led to a resigned attitude toward poverty and injustice. ¶ But by the middle of the 20th century, starting in Brazil and quickly spreading through Latin America, people began to gather into small groups called base communities. As they heard and discussed the Scriptures, the poor began to learn that God loves them, too. They also learned that in situations of misery like theirs, God is not neutral but has “a preferential option for the poor.” ¶ The Hebrew Bible: Liberation theology takes a major cue from the Exodus, where the Hebrews’ God acted contrary to the way other gods acted (allying themselves with kings) because God’s heart is set on justice for the oppressed. ¶ The New Testament: Liberation theology takes a second major cue from the life of Jesus. As in the Exodus, Jesus’ suffering and death reveal that God is with the outcast; Jesus’ resurrection is not only a victory of God’s power over death, but also over injustice. (Although Latin American culture is strongly marked by machismo, the Good News is not limited to men – women in base communities heard that they, too, are included in Jesus’ welcome and embrace.)

(3) The God of life: A member of a base community said, “We discovered that God was different from what we had been taught. We were discovering … the God of life … as one who journeys with us through history… one who is immensely concerned for the poor and the least.” ¶ The true God against idols: In Latin America today, the focus is not on nonbelievers struggling for faith, but on nonpersons struggling for life. The central question is not whether God exists, but how to believe in God in the midst of inhuman suffering. Liberation theology concludes that a God who approves harsh punishment of the poor, and teaches passive resignation to evil, is not the true and living God but an idol imposed by dominant groups in society and church. In the service of the rich and powerful, this image distorts the true reality of the living God. ¶ The God of holy mystery: Karl Rahner and other 20th century theologians noted human yearning for the transcendent, and God’s continued yearning for human beings. Liberation theology opened up a new perspective on this mutual searching. Seeking the mystery of God is not just an intellectual process, but a practical way of life: “Ineffable mystery erupts as love, liberating power, and hope among the poor and oppressed of the earth.”

(4) Fully alive: The martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero took the famous proverb of Irenaeus, “the glory of God is the human being fully alive,” and changed it to: “the glory of God is the poor person fully alive.” God’s glory is made for all human beings, but it is made concrete precisely where abuse occurs.

(5) Praxis of Biblical justice (praxis = practical application): Liberation theology insists on the priority of ‘right practice’ before ‘right thinking.’ That is, rather than starting with correct belief, a Christian has to be already walking with Jesus as a disciple – and that means walking with and for the poor, the despised and the exploited. But ‘God as liberator’ is not just one more image of the divine; this particular image puts a question mark next to every other image of God that ignores those who suffer.

A note on liberation theology: There are still many Catholics who think that liberation theology has been condemned by Rome. While there have been warnings against overusing Marxist analysis (and thus reducing faith to a political, purely earthly dimension), John Paul II said liberation theology represents a ‘new stage’ in the long evolution of theological reflection – and in our present historical situation liberation theology is useful and necessary. Rarely has the core of a theology been so quickly and widely adopted into mainstream church teaching. Unlike older theologies that relegated peace and justice to the next world, liberation theology believes that God’s saving grace applies also to this world. As we see in the life and death of Oscar Romero, this path of discipleship may well lead the church all the way to the cross – the vested interests at stake are that powerful.