© Jay Parini. Reproduced by permission of the author.

QUESTIONS TO GUIDE YOUR READING:

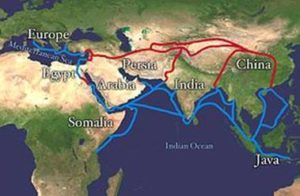

Where did the “silk road” go in Jesus’ day?

Do we live on a “silk road” today?

How does today’s “silk road” change the way we see the world?

Jesus was a Near Eastern event.

– Cynthia Bourgeault, The Wisdom Jesus

The lilies are fallen unto me in pleasant places; yea, I have a goodly heritage.

– Psalm 16:6

ALONG THE SILK ROAD

I recently stood at sunrise on a hill overlooking Jerusalem, with goat bells tinkling in the middle distance. The Mount of Olives loomed in a rising mist, the air tinged with the odor of cypress, not unlike the smell of sage with a twist of lemon. It occurred to me that for thousands of years this prospect had remained more or less unchanged. This bleached landscape was a place where generations of merchants and caravans traveled along the Silk Road in search of wealth and adventure, where foreign armies came and went, where religious passions met, sometimes mingled, often clashed in near apocalypse. The walled city itself was a palimpsest, with many erasures and overwritten passages; it speaks of stratified cultures, layer upon layer: pagan, Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and many iterations of each. It has always, indeed, been a site of placement and displacement, sacred to someone, a major cross roads between East and West, an incendiary point on any map of the world.

For good reason, theologians, historians, and archaeologists have focused intensely on Palestine, especially in the biblical period, and recent work has produced revelations that only enhance the mythic aspect of place in this land. Palestine is a magnet for mythos, the cradle of desert wisdom. And the narrative residue of this area is daunting: a thousand and one tales mingle here, true and partially true, fantastic or realistic. The degree to which ancient Hebrew scripture represents what actually occurred during the millennium before Jesus’s birth, up through the day of his crucifixion in the third decade of the first century is, by itself, a subject that has vexed scholars over the centuries. Yet we know a great deal more about Palestine now than we did only a century ago. “It is no exaggeration to say that since the mid-twentieth century our Western map of the known Christian universe has been blasted wide open.” writes Cynthia Bourgeault, a scholar who has looked closely at the wisdom tradition in the teachings of Jesus. (1) She refers mainly to the discovery of the Gnostic Gospels, such as the Gospel of Thomas, at Nag Hamrnadi in Egypt, as well as the Dead Sea Scrolls in Qumran. In fact, the doors and windows have been flung open by archaeology and textual criticism, and our knowledge of ancient Palestine has multiplied exponentially, bringing new perspectives on the life of Jesus.

A few points we can assume: Jesus was no illiterate carpenter without access to the marketplace of ideas. Living on the Silk Road, a trading thoroughfare between East and West, he would have encountered Hellenistic notions of the soul’s immortality that poured in from the West, from Greece and Rome, and felt the heady winds of mysticism blowing from Persia and the East. Many cultural historians, such as Jerry H. Bentley, have dangled the possibility before us that Buddhism played a role in the shaping of early Christianity, with stories about the Buddha often having parallels in the life and teachings of Jesus. (2) At the very least, religion and trade were binding influences in Palestine at this critical juncture in time, and one can’t overestimate the impact these had on ideas circulating in Galilee at the beginning of this millennium.

In short, the world into which Jesus was born during the time of Augustus Caesar was cosmopolitan as well as Jewish, if reluctantly under Roman authority. The emperor allowed any number of client kings to operate on its behalf: Herod the Great, for instance, kept an eye fixed on Rome for direction as he reigned over an impressive kingdom, where religious culture flourished, centered on the magnificent Second Temple in Jerusalem, which (according to Luke 2:39-52) Jesus visited with his family, who probably joined regular caravans from Nazareth, his home village, to worship at religious festivals, such as the feast of Passover.

This was a desert world alert to every spiritual wind that swept its bright and stony surfaces, a place with “an awesome, all-pervading sense of time and space,” as Joseph Campbell, the great student of world myth, has noted, calling it “a kind of Aladdin cave within which light and darkness, spirit and soul, interplay to create” a world where the human and the divine mingled under the relentless sun. Campbell concludes: “The individual in this world is not an individual at all, but of an organ or part of the great organism – as in Paul or Augustine’s view of the Living Body of Christ. In each being, as throughout the world cavern, there play the two contrary, all-pervading principles of Spirit and Soul.” (3)

A DESERT SOCIETY

Ancient Palestine stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River and adjoining territories: a landscape of olive and fig trees, juniper and date palms, fields of grain, vineyards, fragrant desert flowers and plants, undulating mountains and fertile valleys, with sunlight shimmering off stone buildings – especially the magnificent Second Temple in Jerusalem, which Herod (shortly before the birth of Jesus) enlarged to a size nearly as big as his ego. It became the focal point for Jewish worship, even for civic life in the capital. Indeed, the rebuilding of the Second Temple involved large numbers of people over several decades. According to Joachim Jeremias, a revered New Testament scholar: “When the work began, 10,000 lay workers and 1,000 priests trained for the purpose are said to have been engaged.” (4) That’s a small army. The historian Titus Flavius Josephus (37-100 CE), who remains a major source of information about the early Christian era, described entering the Temple himself and being dazzled by the golden facade that made him blink with admiration and awe. Jeremias says: “Even though we must take the statements of Josephus with critical caution, we cannot doubt that the Temple was built with the greatest possible splendor and provided great opportunities for craftsmanship in gold, silver and bronze. Indeed, on entering the Temple, no matter from what direction a man came, he would have to pass through double gates covered with gold and silver.” (5)

Jesus didn’t enjoy such luxuries, being from a poor village in Galilee, the son of a journeyman (Greek: tekton), perhaps a carpenter or mason by trade: linguists continue to argue over the exact meaning of that term. It’s certain, however, that life outside the Temple itself was anything but lavish for most Jews in this era. They lived in houses of rough-cut stone with flat tiled roofs and unpainted wooden doors. The windows had no screens, of course, so flies were daily companions. These crude dwellings had packed-dirt floors and open courtyards where family and friends gathered for meals and conversation in a peasant society wedded to the agricultural rhythms of planting and harvest times. In the course of any day, Jesus would have seen chickens, sheep, cattle, oxen, camels, goats, horses, and donkeys. The city streets would often have been paved or cobbled, but this was mostly a land of dusty roads and dry, windswept vistas. The smell of dung lingered in the air.

Few people in Palestine at this time could read and write, though devout Jews listened to readings of the Hebrew scriptures, the Tanakh, which included the Pentateuch (or Torah) – the five books of Moses – as well as the Prophets. The so-called Writings, such as the Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, or Job, were later additions to the canonical Hebrew Bible, but they circulated among Jews along with a large quantity of Midrash, a kind of writing devoted to interpreting the meaning of scripture, especially its legal and ethical aspects. Jesus knew these texts well, as we see from his conversations as reported in the gospels, and regarded teaching as a central aspect of his mission: indeed, his followers often called him Rabbi or Teacher. As I noted before, he considered himself a devout Jew with ideas about reforming Judaism, not someone with designs on starting his own religion. It’s significant that he never left a word of writing himself, which meant that his sayings and parables rode on the uncertain breeze of oral tradition, circulating like spores, taking root here and there.

His native language was Aramaic, a Semitic tongue commonly spoken in Palestine at this time, especially among Jews. (It was in the Canaanite family of languages). By the first century, Greek had become the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean, and this was true in Palestine as well, as it had been under the influence of Hellenistic culture since its conquest by Alexander the Great in the fourth century BCE. One assumes that Jesus had some knowledge of Greek, although we lack hard evidence for this. The Romans, who arrived in the middle of the first century BCE, preferred Latin for official purposes, but Latin was rare in the streets (though not unknown). From the trial of Jesus before Pontius Pilate, a Roman prefect, we can assume that Jesus spoke Latin, although his degree of fluency can’t be known. In short, Palestine offered a very complex linguistic stew.

Close to home, Jesus had access to civilized culture. He could have walked to Sepphoris in less than an hour, this city of forty thousand inhabitants and the capital of Galilee, as it lay only a few miles to the northwest of Nazareth. It was the home of King Herod Antipas (until he moved his palace to Tiberias in the 20s CE, when Jesus would have been a young man), and the royal court brought visitors from far and wide. The city perched on the top of a mountain like a bird, hence the Hebrew name for it: Zippori, after tzipor, meaning “bird.” As the discoveries of recent archaeology reveal, it was a wealthy metropolis: the elaborate mosaic floors and colonnaded, paved streets confirm this. It was a busy commercial center, with two markets where traders brought goods from far and wide: woven fabrics from the east, an array of earthenware pots, jewelry, oil for burning in lamps, wooden furniture, beer and wine, fresh fish and fowl, various meats and baked goods, seasonings that included cumin, garlic, coriander, mint, mustard, and dill. Both men and women walked about in loose-fitting tunics, although the men wore leather belts or cloth girdles. Sandals were made of leather and sold in the marketplace. Any number of coins circulated for currency, often minted in Sepphoris.

Of course a substantial sector of the population in Palestine labored in agricultural jobs in this era. They planted and reaped barley or grapes or cared for animals. A smaller group manned fishing boats or worked in what might be considered the clothing industry: weaving cloth for tunics, tooling leather for sandals and belts. Some labored in the olive-oil business, cultivating the orchards or pressing the olives themselves. A number of beekeepers could also be found, as honey was much prized in Palestine, then as now. One could also find a number of butcher shops in any small city or town, and meat from Palestine traveled as far as Athens. Luxury goods, too, attracted any number of specialists, such as jewelers and goldsmiths. Jesus would have been familiar with all of these professions, and he made use of many images from the everyday lives of working men in his parables.

THE CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS SETTING

Galilee in the first century was charged with religious feelings, with competing groups of rabbis – Rabbi Hillel and Rabbi Shammai each founded traditions of biblical study and practice, often in competition for followers. Several devout sects flourished, including the Sadducees and the Pharisees, the Essenes, and the Zealots – the latter a group that didn’t come fully into view until the Jewish revolt of 66 CE, although precursor movements certainly existed. (Jesus not only knew of these sects but possibly belonged to one of them, as Geza Vermes – a pioneering scholar of Judaism and its influence on Christianity – notes.) (6) Each of these sects of Judaism had elaborate rules and habits, although none of them emphasized “belief,” as the term is commonly understood by Christians today. Judaism, then as now, was a religion of practice, not intellectual or emotional assent. You lived as a Jew, following the laws put forward in the Torah. The afterlife could take care of itself.

The Sadducees – the name alludes to Saduc, a legendary high priest during the time of King David – formed an elite of wealthy or influential Jews, including the priests and elders who presided over ritual life in the temple. A worldly group, they got along well with outsiders (travelers from Rome and Greece, Gaul, Egypt and elsewhere) and considered the Pharisees narrow-minded because of their fanatical adherence to Mosaic laws. One occasionally hears of them in the Bible, as when in Matthew 22:23 we read of certain members of this group approaching Jesus: “That same day the Sadducees, who say there is no resurrection, came to him with a question.” In Acts 23:8 we hear that this group had no belief in angels or spirits. Their world was utterly material, focused on the here and now, the physical universe, where ritual mattered as a guide to ethical behavior. They welcomed foreigners into their midst, even non-Jews.

The Pharisees, as their name suggests (the root of the term means “set apart”), wanted nothing to do with outsiders (non Jews or gentiles), and today they would be considered purists. They thought of themselves as “friends” (Hebrew: haberim) of the covenant made by God through Moses with the people of Israel. They first arrived on the scene in the second century before Jesus, and by the time of his public ministry had become a dominant voice in Judaism, with strict rules of admission that included a period when they had to prove their willingness to adhere to ritual laws. (7) They stressed the need to help the poor and asked their members to tithe, giving a tenth of their income to the poor. As opposed to the Sadducees, they believed in the resurrection of the dead and leaned toward prophecy – ideas and tendencies that would influence Jesus in his thinking. And yet Jesus was in conflict with them repeatedly, as when, in Matthew 15:1-3, they complained to Jesus about the behavior of his followers: “Why do your disciples transgress the tradition of the elders? For they don’t wash their hands when they eat bread.” Jesus couldn’t abide such rules, and suggested to his disciples in Matthew 23:5 that the Pharisees did all their works “to be seen by men.” That is, they were showing off, concerned with out ward conformity, not inward transformation.

The Essenes and Zealots were lesser movements in Palestine at this time, but they appealed in various ways to Jesus and his followers. Like the Pharisees, the Essenes advocated Jewish separateness, which they took to an extreme, living in exclusive communities, pursuing repentance and ritual purification. Some lived in mountain caves at Qumran (where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in the mid-twentieth century). They were ascetics who led disciplined, prayerful lives – the Jewish equivalent of monks and nuns. They believed in the human soul and the resurrection of the body, concepts that Jesus would reinforce in his teaching. (There was a branch of the Essenes, or an offshoot, centered in Egypt called the Therapeutae, who strongly encouraged celibacy as a sign of devoutness, even encouraging new followers to abandon their wives and families. They engaged in a practice not unlike psychological counseling, and so they could be considered the ancestors of our present-day therapists.) The Zealots, barely in evidence yet, were less spiritually adept and theoretical. They were political revolutionaries: guerrillas, in effect. (One of the disciples of Jesus, Simon, may have been a Zealot.) In response to what they regarded as Jewish humiliation by the Romans, they wished to drive these pagan invaders from their homeland. As one major scholar of Jewish history has said, “From Galilee stemmed all revolutionary movements,” and these “so disturbed the Romans” that they put pressure on local authorities to repress them by whatever means. (8) Among the legendary heroes of rebellion was Judas the Galilean, a cofounder of the Zealots. When we think about the eventual crucifixion of Jesus by Roman authorities, it’s worth recalling that he associated with people – rabble-rousers, in effect – who resisted foreign occupation. The Zealots never forgot how badly the Jews had been treated by foreign occupations, and they recalled the destruction of the First Temple with a special distaste for their humiliation at the hands of the Babylonians.

For Jews, the past wasn’t really past. When the First Temple (or Solomon’s Temple) was destroyed during the siege of Jerusalem in 587 BCE, significant parts of the Jewish population – largely the middle and upper classes, which numbered about ten thousand people – were swept into captivity by the Babylonian Empire, which vastly outnumbered them. The loss of the Temple – the center of Jewish spiritual and political life – was irreparable and seemed to contradict everything God had foretold in the Holy Scriptures about the triumph of Israel over its enemies, forcing a crisis of confidence, even a crisis of faith. Why had God done this to us? Jews wondered. Had he not made promises about our triumph? From this crisis came many of the mournful psalms and lamentations of the Hebrew Bible. But one also saw the emergence of Ezekiel and Daniel, books of the Old Testament that embody the dream of a return to the homeland, with a theology of salvation in which a Davidic kingdom might be reestablished under the protective eye of God. (Notice that salvation for Jews was a political manifestation of God’s kingdom on earth, not a personal matter, as with many Christians.)

Not surprisingly, it was during the long Babylonian exile that Jews began to conceive of an actual adversary to God, someone who had plotted against his grand scheme for the triumph of Israel, and his opposition helped to explain the trouble at hand. This oppositional figure – not especially terrifying in his first appearances – was called Ha-satan, meaning ‘the Adversary.’ “Although he was a fairly insignificant nuisance in the Hebrew scriptures, he grew in status in later Jewish literature,” says Diarmaid MacCulloch, author of A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, “particularly among writers who were influenced by other religious cultures which spoke of powerful demonic figures.” Ha-satan evolved into Satan, growing in stature during the early Christian era, especially in the Book of Revelation, where he stages a final assault on God’s authority at the Battle of Armageddon. Needless to say, he also took a star turn through the Book of Job – one of the later books of the Hebrew scriptures.

In the wake of the Babylonian exile, for half a century, the First Temple lay in ruins. It was a devastating period but, in retrospect, a fallow time, during which fresh ideas from Greece poured into the region, ultimately affecting early Christian thought in the first century. Alexander the Great had seized control of Palestine and adjacent territories on his eastward expansion, and he opened Judaic doors to Greek philosophical thought while giving the Greek language a solid foothold in the Middle East that it would not relinquish for generations. The dualism of Plato, in particular, with its distinction between the body and the soul, was a legacy that influenced thinkers such as the apostle Paul, whose theological speculations became the foundation of Christian thought. (9) One hears the Hellenistic note, for example, in the idea of “emptying out” or kenosis – the word Paul chooses in his jaw-dropping theoretical effusions in the second chapter of Philippians: “Do nothing out of personal ambition or self-regard but in humbleness regard others as more important than yourself. Let all of you look not only to your own interests but to the interests of others. Have the mind of Christ in yours, thinking of him, who (though he was a god) didn’t consider his equality with God something he could attach himself to. Instead, he emptied himself out, taking on the form of a servant, having been born in the likeness of a man. And he humbled himself further, to the point of death on the cross. For this, God raised him up.” Even here, in my reading, I detect echoes of the rebuilding of Solomon’s Temple, that note of exile, a sense of Paul grappling with Greek ideas in original ways, shaping them to his own theological purposes.

Jesus benefited from the eclectic mix of ideas in Palestine during his coming of age. Yet it could not have been easy for him or any other devout Jew during the Roman occupation at the beginning of the first century, when there were strenuously competing notions about the nature and worship of God and the proper forms that religious practice should take. As the Talmudic scholar Daniel Boyarin recalls: “There were no rabbis yet, and even the priests in Jerusalem and around the temple were divided among themselves. Not only that, but there were many Jews both in Palestine and outside of it, in places such as Alexandria and Egypt, who had very different ideas about what being a good, devout Jew meant.” (10) For his part, Jesus – a man with remarkable skills of spiritual intuition – had his own ideas, and these often conflicted with those of more conventional Jews, especially his notion of self-sacrifice: giving up the ego, allowing God to control our lives. “Blessed are the meek,” he would say, “for they shall inherit the earth” (Matthew 5:5). Before this, one would have to look hard to find anyone celebrating “the meek” or suggesting that they would inherit anything at all, let alone “the earth.”

In a unique fusion, Jesus gathered up many of the loose ends of Judaism, which had frayed badly in Palestine during this era. In a sequence of disruptive sayings and parables, some of which had their origins in Judaic thought and some from elsewhere, he set before the world an ethical code with visionary force, with the power to transform lives and society in spiritual and material ways. But he would do more than that, taking on the role of Messiah or (the Greek word for it) Christ: a luminous figure who became the ultimate symbol of suffering, death. and resurrection. It’s not for nothing that we begin counting a new era from the date of his birth: Anno Domini, meaning the year of our Lord. But he came not only to provide comfort and ethical guidance, but to challenge those around him in ferocious, unsettling, even frightening ways. As T. S. Eliot put it so well in Gerontion: “In the juvescence of the year / Came Christ the tiger.”

QUESTIONS FOR OUR DISCUSSION:

What was the “silk road” in Jesus’ day? Who and what did it connect?

Do we live on a “silk road” today? Who and what does it connect?

How has today’s “road” changed the way we see the world?

NOTES – CHAPTER 1

1 Bourgeault, 16.

2 See Jerry H. Bentley, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

3 Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology (New York: Viking, 1964), 397-98.

4 Joachim Jeremias, Jerusalem at the Time of Jesus, F. H. and C. H. Cave (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1969), 22. This translation was based on the third German edition of this book, published in 1963.

5 Jeremias, 23.

6 Vermes, 62.

7 Jeremias, 251.

8 Simon Dubnow, History of the Jews 1 (South Brunswick, N.J.: T. Yoseloff, 1967),74.

9 See Martin Hengel, Jews, Greeks, and Barbarians: Aspects of the Hellenization of Judaism in the Pre-Christian Period, John Bowden (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980). Hengel wrote numerous books on the Greek influence on early Christian thought and culture.

10 Boyarin, 5.