The 19th century brought a revolution in the understanding of women’s nature and role in society. Throughout the century, two ways of thinking about women were in tension with each other. One way of thinking saw women as human, and focused on the full citizenship that women ought to share with men. The other way of thinking saw women as female, and focused on the special gifts that women brought to their traditional roles as wives and mothers.

In this ferment (and clash) of ideas, the word ‘feminism’ was born (so we should be aware that this ‘new’ word is not a mid-20th century creation, but was coined a century before we were born). Here’s one definition of a feminist: “A person who is in favor of, and who promotes, the equality of women with men, a person who advocates and practices treating women primarily as human persons (as men are so treated) and willingly contravenes social customs in so acting.” (Leonard Swidler in ‘Jesus Was a Feminist’)

Feminism developed from both the secular Enlightenment and Christian roots.

The Enlightenment contributed beliefs in reason, individual freedom, tolerance, progress, personal fulfillment, and rights – political, religious and educational. Protestant Christianity also emphasized freedom of thought for the individual, and revived the idea of the priesthood of the laity. (Catholic tradition insulated itself from these ideas for another century.) Secular feminists demanded changes in marital and inheritance laws, admission to education at all levels, self-determination of the female body, and economic independence. Religious feminists demanded similar rights within the church, challenging the ancient restrictions on women’s right to speak and to teach, and the double standard in morality.

But it was the battle for abolition of slavery in England and the U.S. that gave the feminist movement its first international leaders. In the process of fighting for the rights of black men, women came to understand that they, too, were being kept from their natural rights and their full potential.

Sarah Grimké (1792–1873) and Angelina Grimké (1805–1879) were born into a slave-owning Episcopal family in South Carolina. Both sisters experienced conversion through the great evangelical revival of the early 19th century, and both were disowned by their family when they left the Episcopal Church – Sarah to become a Quaker, Angelina a Presbyterian (eventually Angelina became a Quaker as well). Both sisters became deeply involved in the Quaker work for the abolition of slavery. Sarah published ‘Equality of the Sexes’ in 1837, arguing for moral equivalence of men and women. Sarah became a powerful spokeswoman for the abolitionist movement; Angelina came soon to understand the necessity of women’s rights as well.

As the abolitionist movement intensified, questions were raised about women speaking in public. (At an abolitionist rally in London, women were refused permission to speak, or even sit with the men.) When Angelina Grimké married Theodore Weld in 1838, Sarah became part of their household. After the marriage the sisters became so involved in household duties and parenting Angelina’s children that their public voice was virtually silenced. However, their writings continued – and grew even more radical. Expelled by the Quakers (since Weld was not a Quaker) they stopped worship in any Christian church – calling them ‘places of spiritual famine’. When Sarah died in 1873 and Angelina in 1879, they left behind a radical feminist heritage that foresaw many of the issues concerning the role of women in church and society for the following society.

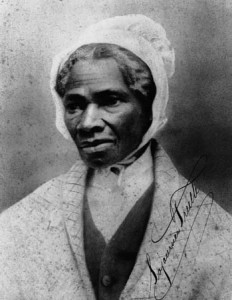

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797 – 1883) lived her first 30 years as a slave. She never learned to read or write – slaves were not allowed to learn to read – but she left an indelible mark on women’s history. Along with Harriet Tubman, she organized the Underground Railroad, and she spoke at the Women’s Rights Convention in 1851. All her learning was oral; ‘visionary literacy’ gave her intuitive religious insights, which she used to critically interpret the Scriptures. She compared the testimony of Scripture with the testimony within herself and concluded that men had inserted many of their own opinions into the Bible: And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and a woman who bore him. Man, where is your part? She concluded that women were quite capable of governing the world. Sojourner Truth contributed to Black feminist exegesis; when black women went to the Scriptures for insight they found comfort, courage and the tools to challenge their culture.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) had been struggling with women’s rights for over 50 years when she published The Women’s Bible in 1895. Stanton probably was unaware that she followed a long line of women exegetes – because women’s history was not accurately recorded (or recorded at all) – the achievements of one generation were often unknown by the next. Women could not build on each others’ insights because these were not available to them. However, there is an amazing unanimity among women over the centuries about two particular biblical passages. In Genesis, women found that they are created in the image of God, and Eve is rehabilitated because she is God’s masterpiece (not God’s ‘first try). In the Gospels, found women witnesses to the Resurrection – which gave women Biblical justification for preaching and teaching.

The Women’s Bible was controversial from the first. Unlike the Grimké sisters, who believed that the Bible was wholly on the side of women, Cady Stanton came to believe that women’s subjection was firmly rooted in the Bible. Her Biblical studies led her to conclude that the Bible was written wholly from a male perspective, and was now being used as a political tool by male churchmen. Most women’s groups disclaimed any connection with The Women’s Bible; Cady Stanton was shocked at women’s reactions to her work.

Women’s suffrage was resisted by both Catholic and Protestant clergy, but in 1919 women finally won the right to vote in the United States. However, by the mid 20th century, the 19th century feminist movement was virtually forgotten, even as women enjoyed the fruits of their foremothers’ labors – especially the rights to vote and to get an education.