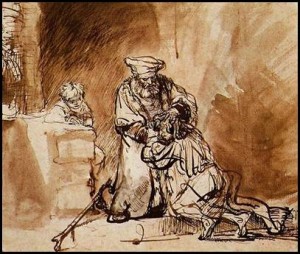

The Return of the Prodigal Son

Rembrandt, 1642

What do you see in Rembrandt’s sketch of the prodigal son? What I see is a father – a father who is falling to his own knees under the heavy weight of his son.

Becoming a parent is one of the life experiences that can teach you about the deep love of God.

As a parent, you feel such deep love for your child, and as their life goes on you keep on loving – it’s not possible to stop. But you don’t have to be a physical parent to feel this kind of this love. Perhaps you’ve adopted a child, helped raise a niece or nephew or a grandchild…. Perhaps you’ve grown very close to the child of a friend… Or maybe you feel the beginnings of this kind of spontaneous love, right now, as you see one of these little ones here at St. Benedict’s.

Most of us, in our different vocations, have experienced this kind of love. We’ve been teachers or mentors for younger people; we became attached to them, we even came to love them at a deep level – and we still love them years later, even when they have disappeared into their own lives.

Life gives every one of us opportunities to love: To watch someone grow up – physically or professionally; to protect them when they’re in danger – real or imagined; to cheer them on when they’re successful, comfort them when they are crushed; to pray for them when they’re hurting, counsel them when they need help – and to step aside when they go their own way.

Rembrandt has to have understood this love – among other tragedies in his own life, four of his five children died as infants. In this painting, the weight of the father’s love for his son is heavy, almost too heavy to bear.

Andrew’s story

We also have a son who went away. Like the son in Jesus’ parable, our son Andrew has plunged, over and over again, into the depths of homelessness and despair.

At 18, Andrew left home to begin his new life in California. First he lived in his car, then moved in with his grandparents, then helped take care of his dying grandfather… After his grandfather died, he had his first psychotic break, but when his grandmother insisted he go for psychiatric help, he went back onto the streets instead.

At 23, he joined the Navy, ending up in the Persian Gulf during the first Iraq War. The night before the war started, he called us. At the urging of the commanding officer, all the men on the ship called their parents, or their wives or sweethearts for a last conversation… But although all on his ship survived, we didn’t hear from Andrew again for three years.

At 27, he did come home again, bruised from life on the streets and clearly mentally ill. While in the Navy, he had other psychotic breaks – and a few months before he came home, the Navy had given him a medical discharge. Like so many veterans with mental illness, Andrew was back on the streets again.

In the 20 years that have passed since then, Andrew has never had a home. He has gone from his own apartments to living on the streets, he has gone on and off medication, back and forth to hospitals and VA group homes… He still dreams of living independently, of being in charge of his own life – and the last time we talked with him he told us that he doesn’t want to talk to his family – not until he’s back in charge of his own life..

And so we have to love him from a great distance. As parents, we not only feel love, but we know we’re called to keep on loving even when it hurts. As a family – parents, a brother, a sister – we know our family was not only created in love, we are called to keep on loving.

As a faith community, created by Christ’s love, we are called to be a people who keep on loving.

Henri Nouwen’s story

Rembrandt painted The Return of the Prodigal Son in the middle of the 17th century. Three centuries later another Dutchman, Henri Nouwen, wrote a book with the same title – a meditation both on Jesus’ parable and on Rembrandt’s painting.* Nouwen was a Catholic priest who influenced Christians from many denominations; Rembrandt probably leaned towards Protestantism, although he never joined a church. But Rembrandt’s painting and Nouwen’s writing, created more than 300 years apart, both show us how Jesus’ parable illustrates God’s love.

In his meditation, Nouwen first identifies with the prodigal son. In The Return of the Prodigal Son, Nouwen writes, [The world has] “many voices, voices that are loud, full of promises and very seductive. These voices say, ‘Go out and prove that you are worth something.’ These voices suggest that I am not going to be loved without my having earned it… They want me to prove – to myself and others – that I am worth being loved…. They deny loudly that love is a totally free gift… (p. 36)

“I am the prodigal son every time I search for unconditional love where it cannot be found. …‘Addiction’ might be the best word to explain the lostness that so deeply permeates contemporary society. Our addictions make us cling to what the world proclaims as the keys to self-fulfillment: accumulation of wealth and power; attainment of status and admiration; lavish consumption of food and drink, and sexual gratification without distinguishing between lust and love…. (p. 38-39) Whatever the son had lost, be it his money, his friends, his reputation, his self-respect, his inner joy and peace – one or all – he still remained his father’s child. And so he finally says to himself: ‘I will leave this place and go to my father.’ With these words in his heart, he was able to turn, to leave the foreign country, and go home. (p. 44) But leaving the foreign country is only the beginning. The way home is long and arduous… While I walk home, I keep entertaining doubts about whether I will be truly welcome when I get there… I still think about God’s love as conditional – and about home as a place I am not yet fully sure of.” (p. 47)

As his meditation continues, Nouwen also identifies with the loving, yearning Father. He writes, “Looking at the way Rembrandt portrays the father, there came to me a whole new understanding of tenderness, mercy, and forgiveness. Every detail of the father’s figure – his facial expression, his posture, the colors of his dress, and, most of all, the still gesture of his hands – speaks of the divine love for humanity that existed from the beginning and ever will be. The near-blind father sees far and wide. His seeing is an eternal seeing, a seeing that reaches out to all of humanity. It is a seeing that understands the lostness of women and men of all times and places, that knows with immense compassion the suffering of those who have chosen to leave home… The heart of the father burns with an immense desire to bring his children home. Oh, how much would he have liked to talk to them, to warn them against the many dangers they were facing. How he would have liked to pull them back with his fatherly authority and hold them close to himself so that they would not get hurt. But his love is too great to do any of that. It cannot force, constrain, push, or pull. It offers the freedom to reject that love, or to love in return. (p. 88)

“It is precisely the immensity of the divine love that is the source of the divine suffering. As Father, he wants his children to be free, free to love. That freedom includes the possibility of their leaving home, going to a ‘distant country,’ and losing everything. The Father’s heart knows all the pain that will come from that choice, but his love makes him powerless to prevent it… As Father, the only authority he claims for himself is the authority of compassion… (p. 89)

And so, Nouwen concludes: “Here is the God I want to believe in: a Father who, from the beginning of creation, has stretched out his arms in merciful blessing, never forcing himself on anyone, but always waiting; never letting his arms drop down in despair, but always hoping that his children will return so that he can speak words of love to them and let his tired arms rest on their shoulders. His only desire is to bless.” (p. 90)

From Rembrandt’s painting, Nouwen learned about the deep joy and unbearable pain of loving – and through Rembrandt’s brush Nouwen heard the call to keep loving when it’s hard, just as God continues to love us.

As children of God, can we keep showing each other how much God loves us? We can learn from each other, as Nouwen learned from Rembrandt; and we can support each other, as we all struggle with the pain of loving.

Because – above all, because – because we are loved, we are called to be people who keep on loving.

* Henri Nouwen, The Return of the Prodigal Son:

A Meditation on Fathers, Brothers, and Sons. Doubleday, 1992.

This sermon was preached at St. Benedict’s Episcopal Church, in March, 2013.

To protect our son’s privacy, it was not posted at the time.

Robert Andrew Ross died in his sleep on February 18, 2014.

Last fall, he called us for the first time in six years, and we had a long and wonderful conversation with him. He asked all about his family and told us about his passions – his computer, I-Pad, television, and his beloved Ohio State teams. He sounded like the ‘REAL’ Andy we’ve all known –

the Andy who loved everything and everybody.

Throughout his adult life, Andy struggled to believe in a loving God.

Like many people with severe mental illness, he felt God judged him very harshly.

In faith, we believe that Andrew is at peace, and that he now knows

that he has always been held in the arms of his heavenly Father.

The Parable of the Prodigal Son

All the tax collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to Jesus. And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, “This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.” So Jesus told them this parable:

There was a man who had two sons. The younger of them said to his father, “Father, give me the share of the property that will belong to me.” So he divided his property between them.

A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and traveled to a distant country, and there he squandered his property in dissolute living. When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that country, and he began to be in need. So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed the pigs. He would gladly have filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating; and no one gave him anything. But when he came to himself he said, “How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger! I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.’

So he set off and went to his father. But while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him. Then the son said to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.” But the father said to his slaves, “Quickly, bring out a robe – the best one –and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. And get the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!” And they began to celebrate.

Now his elder son was in the field; and when he came and approached the house, he heard music and dancing. He called one of the slaves and asked what was going on. He replied, “Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has got him back safe and sound.” Then he became angry and refused to go in.

His father came out and began to plead with him. But he answered his father, “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!”

Then the father said to him, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.”

from the Gospel of Luke (15:3, 11b-32)